Since her arrival in France, Georgia Russell had used the book as a medium, and her cutting technique appropriated different genres, generally textual, known to all. She used novels, book covers etc., where the cut of the scalpel highlights led her to create visual short cuts relating to the dreamlike approach of surrealism or psychoanalysis. The common denominator of all her works is still the cutting out of the medium with the scalpel, a “spark” incision or “flamme plume” (pen-flame), as the critic Anne Malherbe so nicely put it – the equivalent of her pictorial touch, since for her, cutting amounts to drawing (2010, 6). The temporality of her artistic gesture is similar to that of a painter, with whom she compares the regularity and rhythm of her touch. This act, combining gesture and rhythm, time and space, has become fundamental to the work of the artist. But recently Georgia Russell has moved away from the restrained limits of the book to take on much larger formats directly invoking the landscape theme. This article will endeavour to question the nature of these new landscape works. I propose to question the seemingly straightforward significance of these cut-out landscapes. I will first compare and contrast both types of works and will distinguish between the different types of photographs and papers she chooses to work with. I will then interrogate the link between her work and both scientific and literary influences in order to study the visual allusions she makes to the Scottish landscape while working from her French studio.

Nature and Russell’s book sculptures

I have addressed elsewhere the meaning of Georgia Russell’s book sculptures which very much depends on her choice of book titles (2015; 2020). In this digital age, Russell’s book sculptures represent a reflection on the book in its paper form, one shared by an increasingly large number of artists, such as Brian Dettmer, Doug Beube or Guy Laramée, to mention just some of the best known. The art of transforming books has existed at least since the 18th century, with the practice of adding extra-illustrations to biographies called “grangerism” (Heyenga, Dettmer, and Kuhn 2013, 10), after the fashion of personalising book designs by adding clippings to Reverend James Granger’s Biographical History of England (1779). It was explained in detail in a chapter of Eugene Field’s The Love Affairs of a Bibliomaniac in which the author defined it as an unfortunate stage of bibliomania (1900, chap. 12). But book sculpting seems to have become more frequently developed recently, possibly as a reaction to the advent of the all-digital era which questions the purpose of books. This is a practice which demonstrates a particular attachment to the medium, with the works of these artists having a tendency to highlight a certain cultural erosion, in parallel with the so often advocated return to nature. These new transformed books often make reference to the trees from which they originate. One can think for example of the mythical and fairy-tale worlds created by Su Blackwell, presented in glass display cases, such as The Baron in the trees (2011), recalling the forest-like atmosphere of Il barone rampante (1965), the novel by Italo Calvino. One finds a replication in the leaf of the book which turns back into a tree, like a visual amplification of the message the artists seek to transmit by recycling the book-medium through sculpture.

Likewise, the works of Guy Laramée are books where one can see the wood for the trees, so to speak. Under the stylus of the laser cutter used to sculpt the encyclopaedias he uses as material, Laramée’s books become vast mountainous landscapes, depicting a visual erosion, serving as a metaphor of the cultural erosion which forms the subjects of his books, as Laramée himself describes:

The erosion of cultures – and of “culture” as a whole - is the theme that runs through the last 25 years of my artistic practice. I carve landscapes out of books and I paint romantic landscapes. Mountains of disused knowledge return to what they really are: mountains. They erode a bit more and they become hills. Then they flatten and become fields where apparently nothing is happening. Piles of obsolete encyclopedias return to that which does not need to say anything, that which simply IS. Fogs and clouds erase everything we know, everything we think we are. (n.d., Guy Laramée)

Georgia Russell’s approach differs from those of her fellow artists, since she sculpts the book with the help of a scalpel, without the use of machines, thus limiting her possibilities to work on thick volumes. It is also perhaps why she often only retains the covers of the works that she uses. Hence, when the artist chooses to sculpt a dictionary rather than the cover page of a work, it is to “liberate” the book, while never losing sight of its initial function. This approach is in contrast therefore to some of her colleagues, who alter the function of the book by transforming them, for example, into landscapes, or by reifying them in the form of objects. A contrario, the dictionaries she chooses retain the notion of their original function: the covers or the edges of the work, where the titles are still visible, constitute the principal axis from which words issue forth like flying sparks, taking on a literally tangible form, (e.g. Hachette Dictionnaire anglais français 2009b).

Besides, if the medium that Georgia Russell uses is often found or retrieved, the artist’s book sculptures do not have, in contrast to those of landscape book artists, a materiality of pattern and paper directly recalling the wood from which the book was derived. Despite the importance of the book in the work of the artist, this form of cultural nostalgia is not what distinguishes the work of Georgia Russell; it is rather a more introspective emotion with regard to landscape, reflecting a parallel in her approach to language. The artist’s book sculptures usually take the title of the work as a starting point. Initially the artist saw in the titles just graphic and cryptic signs:

I didn't speak French, and so I saw the language in a different way, in a design, graphic way, as marks. (Vernon 2005)

But she started to transform them into something else, to materialise the book in totemic figures so as to free it from its initial content and humanise it. And this evocation of the human emotion is emphasised when the artist retains the book title as a title for her own works. The title thus fulfils a double role, since it appears both on the cover and as the title of her work. Georgia Russell also obtains a visual art re-contextualisation of the original work, when she amplifies in visual terms the meaning of the chosen title, be it by the combined colours and titles she uses (red for Le Désir, 2009d) or the shapes she decides to put forward. For example, L'irréparable (“Irreparable”, 2009e), presents an irremediably torn cover. There is the same effect with La traversée des apparences (which is the French title for Virginia Woolf’s The Voyage Out but means “Walking though appearances” in French, 2009c) where, behind the jacket, one can make out another front page inciting us to look for something further, beyond this initial cover. We are no longer in the arbitrariness of the undecipherable sign or symbol, but actually in a subtle overlapping of the form and the words to be found, in an even more subtle manner, in her landscapes.

Georgia Russell’s “inscapes”

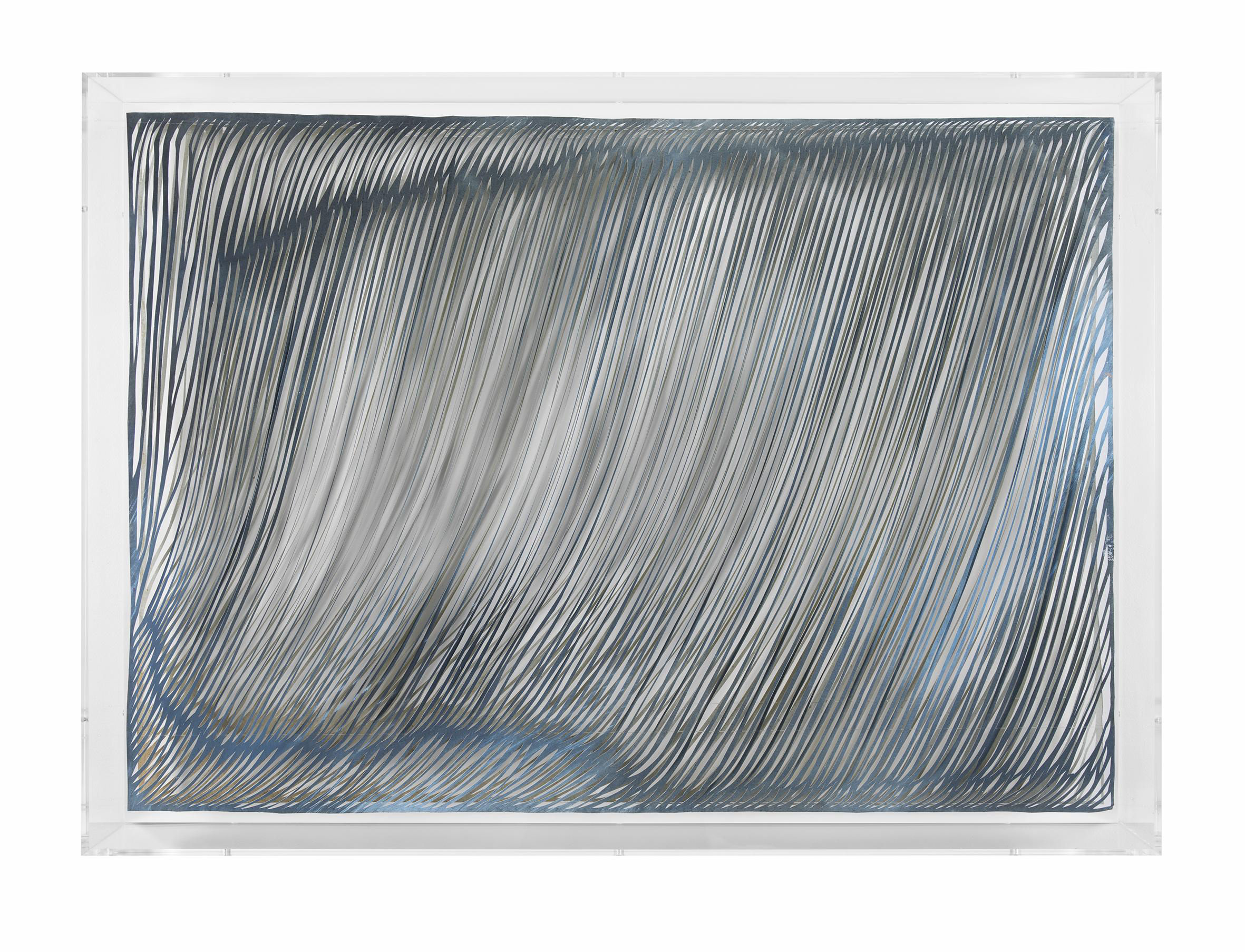

While her book sculptures questioned in particular the meaning of book titles and rarely nature directly, Georgia Russell has been exploring landscapes for some time in formats much more imposing than before that are not any longer made out of books. Through the unfurling which characterises them, these artworks recall the book covers I have mentioned above and in a previous article, but this time in augmented dimensions which emphasise her introspective interest in nature.

For these landscapes, the artist has used different types of materials, from paper to canvas, some found and others especially made. In 2011 she worked from a collection of photographs of forest and marine landscapes kept in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, which she reprinted on Kozo paper. The artist appropriated these 19th century landscape photographs and engravings with the distinctive rhythmicity of the pen flame incision which is her trademark. Since the beginning of her career, Russell has cut and augmented materials to look beyond the simple outward appearance of the print or the photograph. She goes as far as placing footprints, like those she might leave on the beaches of North-East Scotland – the flat beaches of Sindhorn, near Elgin where she walks several times a year when returning home – , thus imposing to an even greater extent her own mark on the photograph, transformed by her rhythmic incisions (2011c). These landscapes however are most of the time devoid of people, as in the landscape tradition which came to the fore in the 19th century, where man stands aside before the splendour of the landscape. In fact, one can wonder how far the pictures she uses are emptied of their original content once they have been sliced and transformed into lacework or given a new, flowing life. Some photographs also come from the artist’s personal collection and her immediate environment. The Cerisiers series (2013), shows the changing of the seasons being acted out before her, from the windows of the former industrial nacre workshop where she lives and works, between Paris and Beauvais. The photographs taken by her assistant from inside the workshop are printed, enlarged, lacerated then split apart, stretched between two invisible threads, to create the elusive movements of the wind and of time going by.

In order to characterise her work, the artist said she particularly appreciates the word “inscape” which she finds similar to the idea of personal visions or hallucinations used by the British neurologist Oliver Sacks when he talked about the ways blind people imagine images of things and or of their own bodies. As a matter of fact, in Hallucinations, Sacks does not exactly resort to the word “inscape”, which is a concept about individual identity used by English poet Gerard Manley Hopkins. Rather, Sacks uses the notion of “inner eye”, saying that “the deprivation of normal visual input can stimulate the inner eye instead, producing dreams, vivid imaginings, or hallucinations” (2012, 34). In A Leg to Stand on (1984) and Hallucinations (2012), Sacks based his writings on experiences with his neurological patients and observed that, besides the impairment of vision or body parts, they also had positive symptoms such as hallucinations in the blind area or felt the presence of phantom limbs. But Georgia Russell felt that the word inscape “summed up a kind of landscape particular to oneself and the memory of an image, place or time” (England&Co website). Hence her landscapes, fixed in time and/or by the photograph, come to life, just like the emotion the artist felt when observing them. A human presence is there, lurking in the background, in this act of memory and observation. And it is when she is back in France that the artist brings back to life the Scottish landscapes she misses, thanks to oil sketches she does outside and which work as preparatory material. She said:

When you go to Scotland, the landscapes are pure, empty, changing, windy, the wind is blowing in the trees. I like to show the animation of the landscape by another force. It is about observation, paying attention to the marvellous. (Béchard-Léauté 2016)

We might characterise this practice as “pre-impressionist”, since she favours work based on memory rather than being in situ. She also returns to the more traditional materials of painting, such as the use of acrylic and spray-paint on canvas. But, with this retrospective method, where the artist re-works her sketches once she is back in her workshop in France, we can also perceive the nostalgia of a world she misses: the Scotland she left at the age of 22, initially for London after her studies in Aberdeen, then for France.

Just after leaving the United Kingdom, Russell’s references to Scotland were more straightforward. A series of transformed book covers used famous Scottish books highlighting the clan tradition (Clans and Tartans of Scotland, 2002a) and the Scottish fighting spirit as in The Kingdom of Scotland (2004), Scotland the Brave (2007). She also used Scottish books that had a link with France such as The Tartan Pimpernel (2002b) written by Donald Currie Caskie, a reverend of the Church of Scotland best known for his exploits in France during World War II. Similarly, a map of Scotland was entitled Ecosse (2009a), reminding us both of Scotland’s historical connections with France and with the artist’s country of residence.

In the work, My skeleton (2001), she appropriated the map of Scotland, being at one with it through her sculptural gestures and the possessive pronoun of the work title. Maps are not very frequent in Russell’s work and can be political, although it is not the case here.1 As time went by her references to Scotland became less direct and more landscape orientated, as if it was not so much her country she missed, but the memory of the incessant changes in the landscape brought on by the variability of the Scottish climate. Sometimes, as with the four pieces, North, East, South, West (2011a) – which allude to the proverb “North, East, South, West, Home is the best” – her landscapes attain a degree of self-effacement, even in terms of colour, as in this series of white pieces cut out at the back of musical scores. A recent series entitled Furrow Study I, II and III (2016b), similarly refers to the direction of the wind using once again a plain white background. One understands quite clearly that the formal unity of Russell’s landscapes does not stem from their representation but from a need to grasp the invisible elements which drive them: the currents in the sea and the flowing winds of the North, East, South, West series which seem to shake the barley of the Scottish countryside. Thanks to the creation of cavities which her cutting technique allows, Russell manages to carve the presence of the wind into paper or canvases, in the manner of Giacometti who sculpted human shapes by hollowing out his white plaster casts. In her works, it is also the absence of matter which paradoxically acts as a presence, as was the case for the phantom limbs Oliver Sacks studied in Hallucinations and A Leg to Stand On.

Literary reminiscences of landscape

In the words of Georgia Russell, as in the attention paid in her art to the forces of nature, one can also distinguish a form of romanticism. One is not surprised moreover to find, opposite her biography in the retrospective catalogue her gallery has already published, a photograph, taken from behind, of the artist facing a Scottish beach (Béchard-Léauté, Oncins, and E. Buhlmann 2015). Whether deliberately or not, the photographer seems to be referring as much to the discretion of the artist as to the celebrated paintings of men – or women – in the face of nature by Caspar Friedrich, e.g. his famous Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818). There is indeed a coincidence, in the real meaning of the term, between the powers of observation and re-transcription of the artist and the natural forces of the landscapes she works on. Behind the words of the artist and her literary influences, one divines the tradition of romantic landscaping, inseparable from thoughts on the sublime, initiated by the Theory of heaven by Kant, and the aesthetic, pre-romantic and romantic considerations of Schiller and Burke. Here, man, in contrast to the Renaissance, gradually steps back from the all-powerful notion of nature, as recently demonstrated by Thomas Schlesser in his book entitled L’Univers sans l’homme (“Universe without man”, 2016) – which shows how the arts in the broader sense, since the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution, in the middle of the 18th century, through to our post-industrial era, have opposed the anthropocentrism which had characterised the arts since the Renaissance. Some see, in this over-powering presence of the landscape, whether it be pastoral or apocalyptic, an excessive aestheticisation of the motif, removed from any philosophical investment. Schlesser, however, has shown how much this underlying and enduring tendency of art towards the disappearance of the human figure, raises issues of general interest by participating in the insistent reflections concerning the rightful place of man in the scale of life.

Thus the art of Georgia Russell belongs to this tradition of a gradual withdrawal of human figures from the landscape that one already found with painters such as Constable and Turner, who enacted the separation between the genres of landscape and history, and with the Romantic writers who, after 18th century philosophers, acknowledged the presence of the sublime in nature. For Georgia Russell, the enchantment lies in this constant regeneration of nature which the artist also likes to find in literature. In an interview with the present author, she actually claimed Shelley and Keats as sources of inspiration for her landscapes, and more precisely a poem by Shelley entitled “The Cloud”, about the regeneration of nature, the fact that nothing ever stops, and the cyclical aspect of nature. The narrator in this poem is the cloud, which describes, in six rhymed stanzas, and with an eminently visual, joyful and pastoral text, the diversity of its work on earth. There is an emphasis on the cycles of nature and the eternal omnipotence of the cloud:

[…] I pass through the pores, of the ocean and shores;

I change, but I cannot die –

[…] And out of the caverns of rain

Like a child from the womb, like a ghost from the tomb,

I arise and unbuild it again. (Shelley 1993, 57).

Another text further clarifies what motivates Russell in these Scottish landscapes. It is the first paragraph of The Waves by Virginia Woolf, which the artist was anxious to have featured in the retrospective catalogue which Galerie Karsten Greve prepared for her. While the editorial format of the gallery’s catalogues did not allow the artist to express herself in the first person, – or, as we would have liked, in the form of an interview –, she insisted that this text appeared as an incipit to the catalogue, as a very personal testimony to the content of her art.

The Waves deals with the issues of time and death and was regarded by Marguerite Yourcenar as Virginia Woolf’s masterpiece as it is the most intense, poetic and experimental of all her works (1982, 7). The main text, where each character speaks formally his or her own thoughts, is introduced and divided by sections of lyrical prose describing the rising and sinking of the sun over a seascape of waves and shore:

The sun had not yet risen. The sea was indistinguishable from the sky, except that the sea was slightly creased as if a cloth had wrinkles in it. Gradually as the sky whitened a dark line lay on the horizon dividing the sea from the sky and the grey cloth became barred with thick strokes moving, one after another, beneath the surface, following each other, pursuing each other, perpetually. As they neared the shore each bar rose, heaped itself, broke and swept a thin veil of white water across the sand. The wave paused, and then drew out again, sighing like a sleeper whose breath comes and goes unconsciously. Gradually the dark bar on the horizon became clear as if the sediment in an old wine-bottle had sunk and left the glass green. Behind it, too, the sky cleared as if the white sediment there had sunk, or as if the arm of a woman couched beneath the horizon had raised a lamp and flat bars of white, green and yellow spread across the sky like the blades of a fan. Then she raised her lamp higher and the air seemed to become fibrous and to tear away from the green surface flickering and flaming in red and yellow fibres like the smoky fire that roars from a bonfire. Gradually the fibres of the burning bonfire were fused into one haze, one incandescence which lifted the weight of the woollen grey sky on top of it and turned it to a million atoms of soft blue. The surface of the sea slowly became transparent and lay rippling and sparkling until the dark stripes were almost rubbed out. Slowly the arm that held the lamp raised it higher and then higher until a broad flame became visible; an arc of fire burnt on the rim of the horizon, and all round it the sea blazed gold. (1982, 639)

When reading this very visual first paragraph from The Waves, one perceives all the power of the elements. Russell’s last exhibition entitled Time and Tide – as in the expression, “Time and Tide wait for no man” – can be construed with Russell both in the literal sense, in the face of the force of the represented elements, and in the figurative sense, so inexorable is the feeling of passing time, as in The Waves by Virginia Woolf. The artist had already referred to this novel in The Waves (2011b), a piece by Russell which looks like the reverse of the North, East, South, West series, where instead of cutting out the musical scores, she pasted false eye lashes on them. But the resemblance of Woolf’s text with the works of the artist presented in the Time & Tide exhibition at Galerie Karsten Greve in Paris in 2016 is more strikingly evident, in particular with the third sentence describing the thick strokes perpetually moving beneath the surface of the sea, and also with the references to fibres that the air seems to tear away from the sea. Woolf’s numerous alliterations also parallel Russell’s abundant strokes. It is plain that what matters to Russell, as much as it did to Woolf, is not only to capture the ephemeral nature of shapes, the movements of the wind, streams and colours – as with her Stream Studies of 2015 and Daystream series of 2016 – but also the reoccurrence of natural cycles which extenuate and temper temporal finiteness. In our November 2016 interview, the artist said:

This text is exactly how I feel about the landscape, exactly what I want to represent in my work, the various layers, the different depths, also the fact that ideas come and go, that when an idea is lost, it comes back after. (2016)

Hence Russell’s recent works play on the changes of view, on chromatic changes. These works have been likened to the kinetic works of “Bridget Riley, who played with the perception of the spectator through the use of line, colour and elementary shapes” (Mekouar 2016, 10). But it is above all the fluidity of the materials and patterns, as well as the circularity of time, which Russell puts to the fore in a sole framework. The formal harmony which her cutting technique imparts to the vertical flowing streams she depicts could also recall the formal unity recommended by William Turner in his Sixth conference in 1811 who recommended to abolish any hierarchy within a painting, placing the action of figures and the background on the same level. In fact, her recent, much larger works, bring to mind stormy seas and changing lights where time and space coincide, just like in Turner’s works. Escarpement (2016a) and Highground (2016c) whose movement can only be vertical, due to gravity, also seem to show the recurring shadows of the passing clouds. As Mouna Mekouar noticed: “Her daily dialogue with colour and nature – the changes of the sea, the tides, modulations of light over the course of the day, the movement of trees, the passing of clouds – is a source of inspiration” (2016, 12).

Time, space and their memory are enduring features of Georgia Russell’s work, firstly by her repetitive, flowing and cyclical technique, then by the references to other literary landscapes that her works convey. Landscape painting was for a long time considered as a minor pictorial genre in the hierarchy of arts, before the appearance of the English and French pre-romantic and romantic landscape artists that coincided with the Industrial Revolution. In the 20th century conceptual artists also re-appropriated landscape, for instance through walking, installations and sculptures, but less by painting. Georgia Russell’s art re-appropriates landscape by combining both pictorial and sculptural gestures. Although it does not call for the discursive demands of conceptual art, her work relates to the universal experience of space and time in landscape. One can also feel a more personal sense of urgency in Russell’s works that is not directly related to the landscape theme but rather to the artist’s success. Her very simple but effective Precipitation I (2015a), is both about time and water. But as the title indicates when read both in French and in English, it has a double meaning: it is both about the gathering of water and waiting hurriedly for something. The artist confided that she liked this work so much that she tried to make another entitled Precipitation II (2015b). In fact, the artist has met with such success that all the works she produces are sold to an increasing number of collectors. As a result, Georgia Russell can only keep certain traces of her own works, which means that she is herself caught up in a cycle, that of perpetual creation.

Bibliography

Béchard-Léauté, Anne. 2016. “Interview with Georgia Russell.” Interview.

Béchard-Léauté, Anne. 2020. “Georgia Russell’s Scalpelled Books as Visual Metaphors.” Interfaces. Image Texte Language, no. 43 (July):113–21. https://doi.org/10.4000/interfaces.936.

Béchard-Léauté, Anne, Valentine Oncins, and E. BuhlmannBritta. 2015. Georgia Russell. Galerie Karsten Greve. Saint-Moritz, Paris, Cologne.

Blackwell, Su. 2011. “The Baron in the Trees.” Artwork.

Calvino, Italo. 1965. Il Barone Rampante. Torino : G. Einaudi,

Field, Eugene. 1900. “12.” In The Love Affairs of a Bibliomaniac. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons. http://www.sudoc.abes.fr/cbs/xslt//DB=2.1/SET=1/TTL=11/SHW?FRST=13.

Friedrich, Caspar David. 1818. “Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog.” Artwork.

Gallery, England&Co. 2014. “Georgia Russell: Cutting Through Time.” England & Co Gallery. https://www.englandgallery.com/georgia-russell-cutting-through-time/.

Granger, James 1723-1776. 1779. A Biographical History of England. The third edition, with large additions and improvements. London: printed for J. Rivington; Sons, B. Law, J. Robson, G. Robinson, T. Cadell, T. Evans, R. Baldwin, J. Nicholl, W. Oteridge,; Fielding; Walker.

Heyenga, Laura, Bryan Dettmer, and Alyson Kuhn. 2013. Art Made from Books: Altered, Sculpted, Carved, Transformed. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

Laramée, Guy. n.d. “Artist Statement.” Guy Laramée. Accessed February 3, 2017. https://guylaramee.com/artist-statement/.

Malherbe, Anne. 2010. “Le Scalpel.” In Georgia Russell, Dukan&Hourdequin, 5–6. Exhibition Catalogue. Marseilles.

Mekouar, Mouna. 2016. “Through the Frame.” In Georgia Russell: Time and Tide, 5–12. Paris: Galerie Karsten Greve.

Russell, Georgia. 2001. “My Skeleton.” Artwork.

Russell, Georgia. 2002a. “Clans and Tartans of Scotland.” Artwork.

Russell, Georgia. 2002b. “The Tartan Pimpernel.” Artwork.

Russell, Georgia. 2004. “The Kingdom of Scotland.” Artwork.

Russell, Georgia. 2007. “Scotland the Brave.” Artwork.

Russell, Georgia. 2009a. “Ecosse.” Artwork.

Russell, Georgia. 2009b. “Hachette Dictionnaire anglais français.” Artwork.

Russell, Georgia. 2009c. “La traversée des apparences.” Artwork.

Russell, Georgia. 2009d. “Le Désir.” Artwork.

Russell, Georgia. 2009e. “L’irréparable.” Artwork.

Russell, Georgia. 2011a. “North, East, South, West.” Artwork.

Russell, Georgia. 2011b. “The Waves.” Artwork.

Russell, Georgia. 2011c. “Yellow Horizon.” Artwork.

Russell, Georgia. 2013. “Cherry Trees.” Artwork.

Russell, Georgia. 2015a. “Precipitation I.” Artwork.

Russell, Georgia. 2015b. “Precipitation II.” Artwork.

Russell, Georgia. 2016a. “Escarpement.” Artwork.

Russell, Georgia. 2016b. “Furrow Study I, II, III.” Artwork.

Russell, Georgia. 2016c. “Highground.” Artwork.

Sacks, Oliver. 1984. A Leg to Stand on. New York: Summit Books.

Sacks, Oliver. 2012. Hallucinations. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. http://banq.lib.overdrive.com/ContentDetails.htm?id=9200B916-455F-4842-80DE-788A82808B37.

Schlesser, Thomas. 2016. L’univers Sans L’homme. Vanves: Éditions Hazan.

Shelley, Percy Bysshe. 1993. Ode to the West Wind and Other Poems. Dover Thrift Editions. New York: Dover Publications.

Vernon, Polly. 2005. “Introducing... Georgia Russell, Artist.” The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2005/jan/16/art1.

Woolf, Virginia 1882-1941. 1982. Les Vagues. Paris: Le Livre de poche.

Woolf, Virginia 1882-1941. 2012. Selected Works of Virginia Woolf. Ware: Wordsworth Editions.

But it was the case for the work Britain: March 2003, now at the Victoria and Albert Museum, subtitled Britain on Iraq. The work represents the map of the UK hollowed out and placed over a map of Iraq, thus referring to Tony Blair’s decision to invade Iraq without the authorization of a U.N. resolution.↩