Steve Tomasula’s VAS, an Opera in Flatland (2004) explores and questions forms of representation to show how they make sense, in ways that keep changing with the context of their reception, and in a variety of fields, the aesthetics of this novel reach into the epistemological, political and ethical realms, to name but a few. In the verbal group “making sense”, “to make” is to be understood in the concrete sense of producing, in the arts and crafts worlds, as indeed reading VAS is a rich sensory experience allowing the readers an acute awareness of the activity of perception involved in reading. While we have long entered the age of the virtual, VAS offers an exploration of our relations to the materiality of texts and books as well as to bodies of all kinds, first and foremost our bodies, which are affected by reading. As the reader becomes aware of the effects of the book’s aesthetics upon her, the reading activity is revisited while the possibilities opened out by the novel genre are brought to the fore. This paper aims at showing how VAS both stages and generates a radical questioning of the novel genre as well as of reading, thus calling for new notions and definitions in the field of literature and criticism. Reading VAS will be considered first as a visual experience, then as a sound experience and finally as an experience in space and time, all being intricately intertwined – vision, hearing, space, time – and only separated here for the sake of investigation.

Circle has suffered so much to give birth to little Oval after several miscarriages that she no longer wants to run such risk. She asks her husband Square to take “[h]is turn” (Tomasula 2004, 14) and undergo a vasectomy. This launches Square into a meditation over creation – his own threatened reproductive power and his creative practice as a writer. VAS opens as Square is wondering how to finish his novel, so that this is a book about endings as much as beginnings: the end of an era, of a certain type of relating to books and bodies, and the beginning of new modes of relation.

A Visual Experience

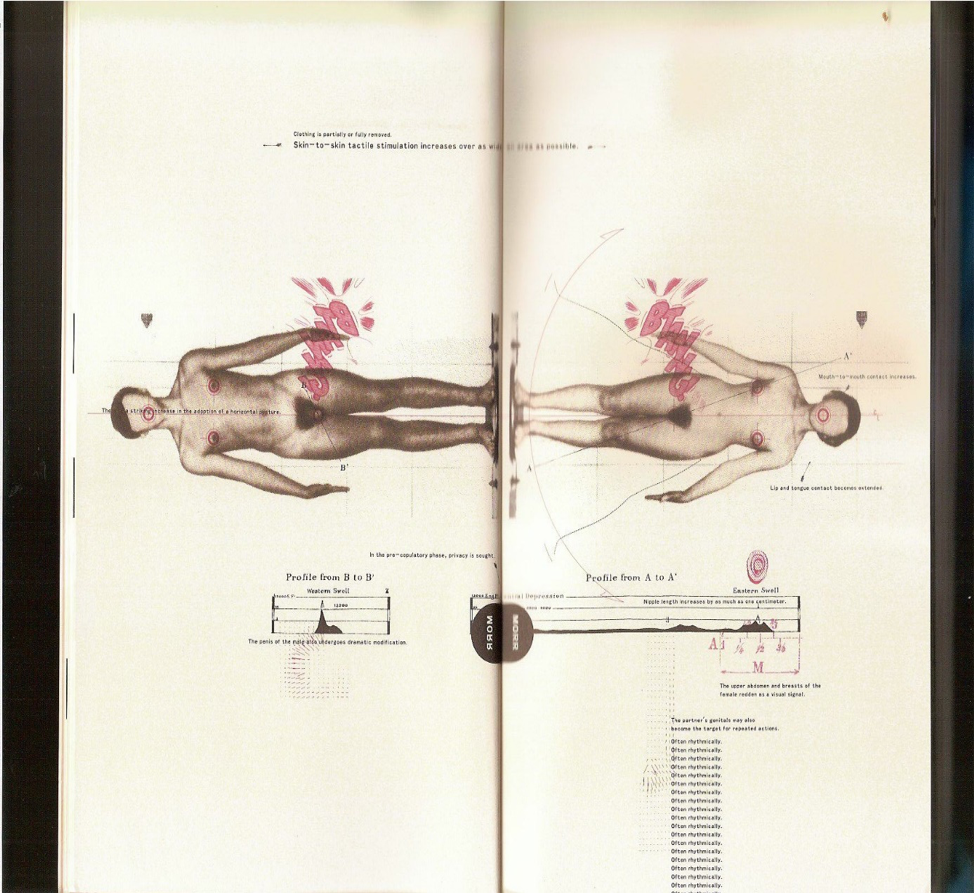

From its very cover, the book is assimilated to a body, with its veined skin, and pages the color of flesh or in shades of body fluids. This continued metaphorizing or correspondence process throughout the book creates an alert reader, on the lookout for parallels between book and body, letters of the DNA and of the alphabet, genealogy and etymology. For instance, in their family tree, the genealogy of Square and Circle may be equated with the etymology of the words “square” and “circle”, the combination of which rather weirdly gives “oval”1. Even Circle’s leitmotif to refer to the vasectomy, “just a little editing” (Tomasula 2004, 192) assimilates his body to a book2. The reader’s relation to the book is thus made more immediate – more obviously tactile, as she holds a book-body in her hands – and more distant, as she is on the watch for accretions of meaning, ambiguities, suggestions and double entendre.

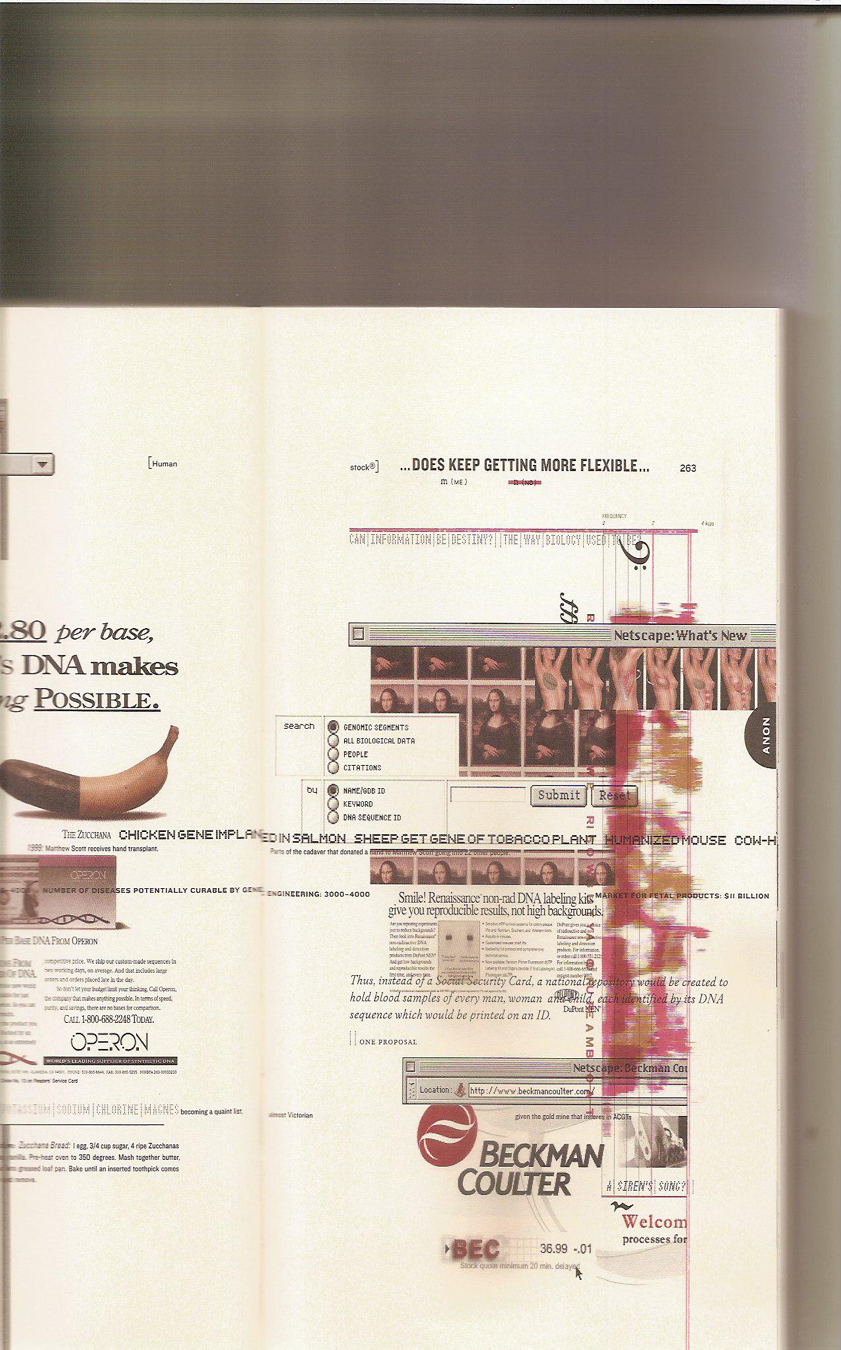

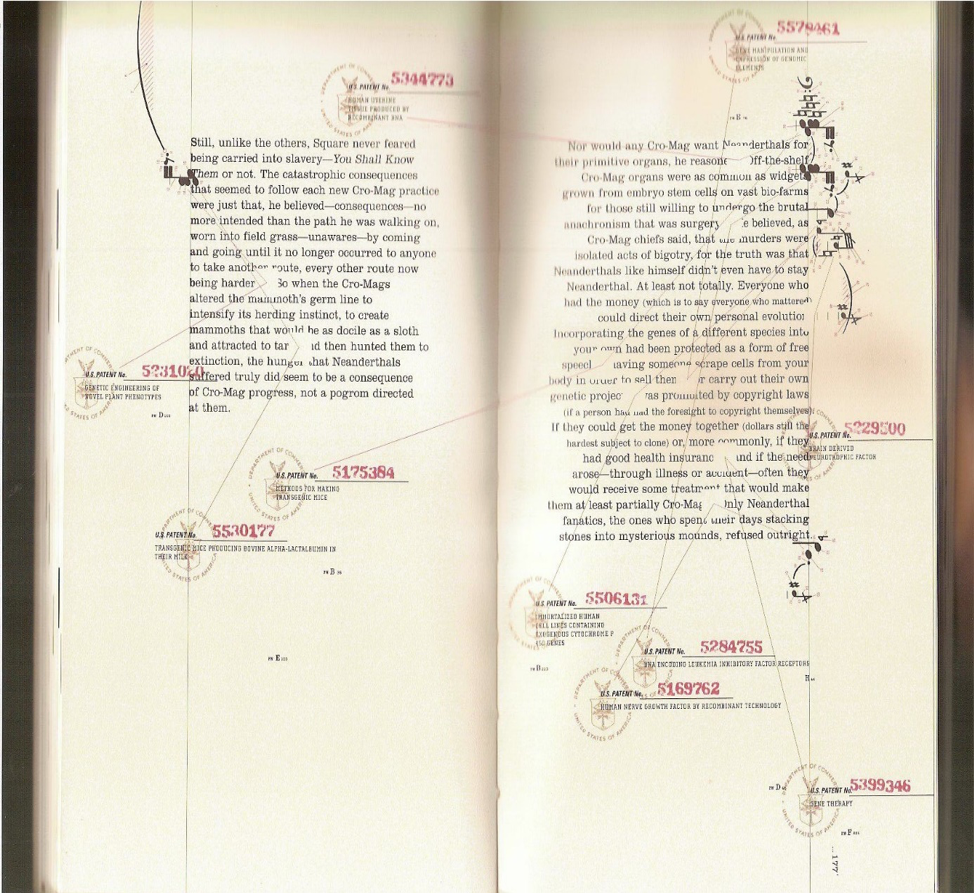

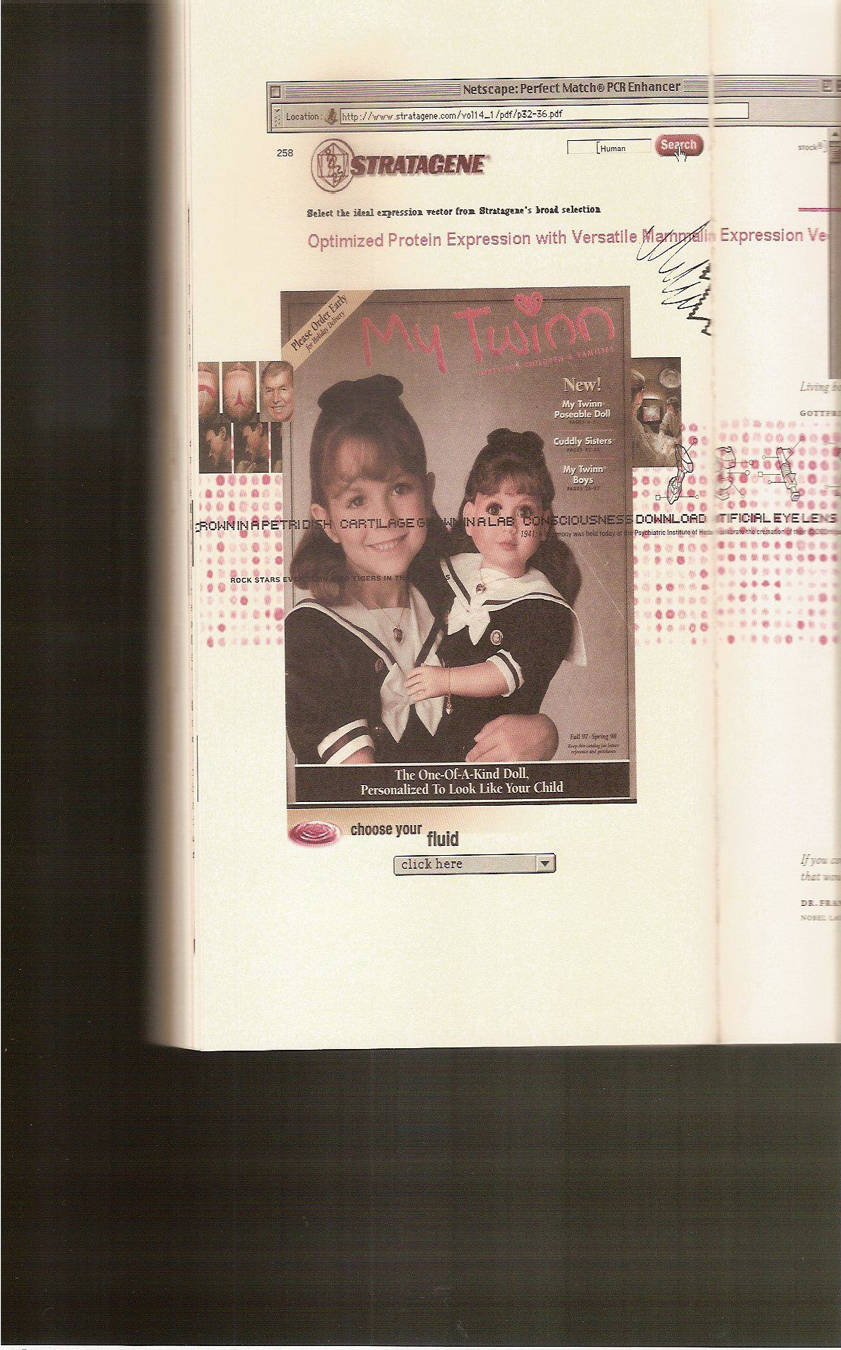

This book-as-body shows a variegated aspect suggesting the changing rhythms and colors of life. Often called an artist book, VAS includes images, graphs, tables, captures of computer screens, while also playing on typography, fonts and generally on the layout of the page.

Such diversity by contrast brings to the fore the ways in which representation modes and devices work upon us, ways of which the reader should be aware, as well as of their aims, so as not to be fully deceived by them: VAS partly is a clarifying enterprise3, exposing seduction strategies and teaching discernment.

This goes through distancing and subverting, for instance the order in which we read.

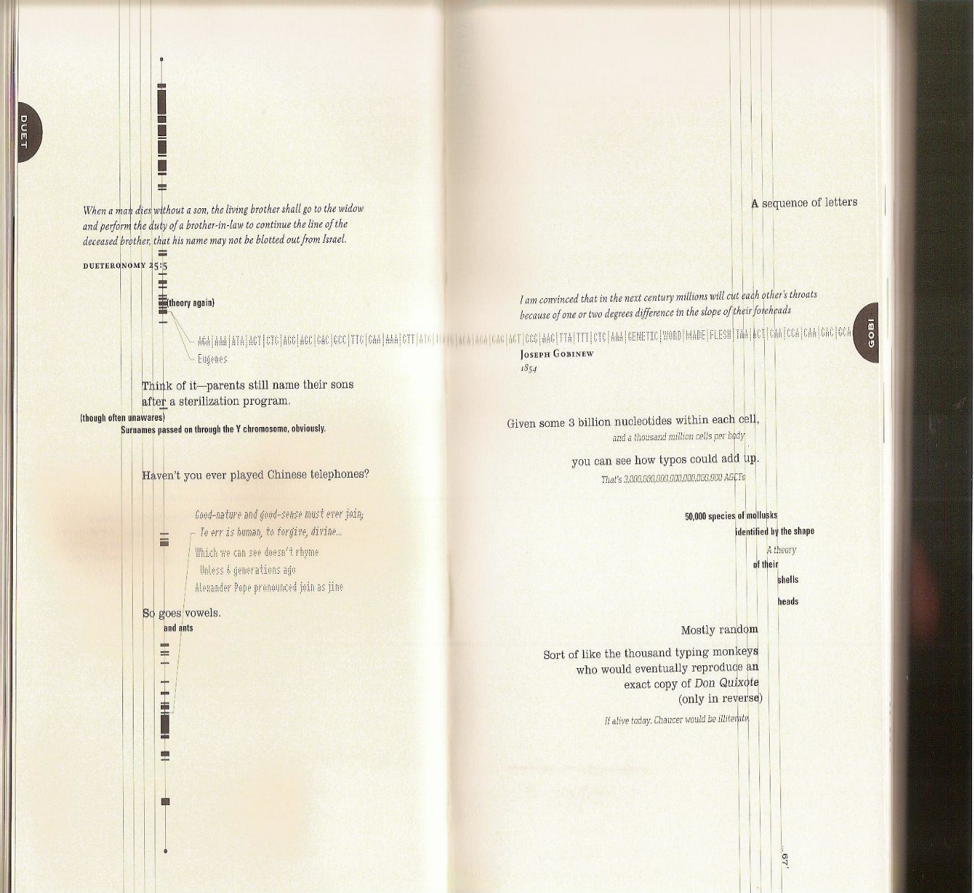

The reader has to choose where to start on the page, or in what order to read the segments lying on each side of the vertical lines: should one read the left half first, or from left to right and turn to the next line? Or again follow the vertically aligned letters in bold type, at the center of the upended stave that gives a margin to many a page?4 Other pages combine text and pictures, thus requiring shifting modes of apprehension. The multimedia nature of VAS disrupts the linear discovery of the page together with the linear unfolding of the story. Especially as the reader progresses into the novel, aesthetics grow more complex, giving a sense of confusion aptly representing a possible reaction to the contemporary proliferation of messages.

The reader becomes aware how her gaze moves on the page, as well as of her position in space and time within her culture and in relation to other cultures: VAS carries out a process of de-centering and upsetting hierarchies.

Indeed the fragments in lower-case letters floating around the vertical axis first seem to offer marginal comments. But more often than not they appear as extensions of text making for alternative readings; they are thus endowed with a political dimension, as they disrupt the unique, linear meaning put forward by the master narrative. For instance, such marginal phrases as “For the good of the patient” (Tomasula 2004, 122) of “For the good of society” (Tomasula 2004, 117, 128, 129, among others), which are leitmotifs in the book, question the motivations of the eugenic policies carried out by the government on ironically called “mollusks” (Tomasula 2004, 120, 121, 128, among others) actually referring to human beings. The text turns into a polyphony, made visible through the use of various fonts, in the following example italics and roman type:

On the page in his lap, the

truth world he’d been writing into existence was

slicing membranes

dead-skin white-paper sans corpuscules (Tomasula 2004, 10)

The impossible unity of the text, together with its play on limits and margins, make for a reflexion on exclusion, almost an act of protest against the uniformity brought about globalization, also conveyed through the resort to mixing genres and media. By steeping the reader into the multiple, VAS relocates each and every one of us in space and time by recalling that man is but one ring in a chain. As the animated structures of VAS encourage a constant shifting of scales and points of view, they allow to embrace diversity rather than blindly follow the diktats of the mainstream. The floating fragments in the earlier quoted passages may also read as making up a poem of their own, offering a counterpoint to the main narrative, punctuating it with marking sounds, images and ideas, enhancing it in a way, through contrasts or corroboration. Several patterns superimpose in the reader’s perception of the book, turning it into a rhythmic and musical piece that keeps mutating under the reader’s eyes and in the reader’s mind.

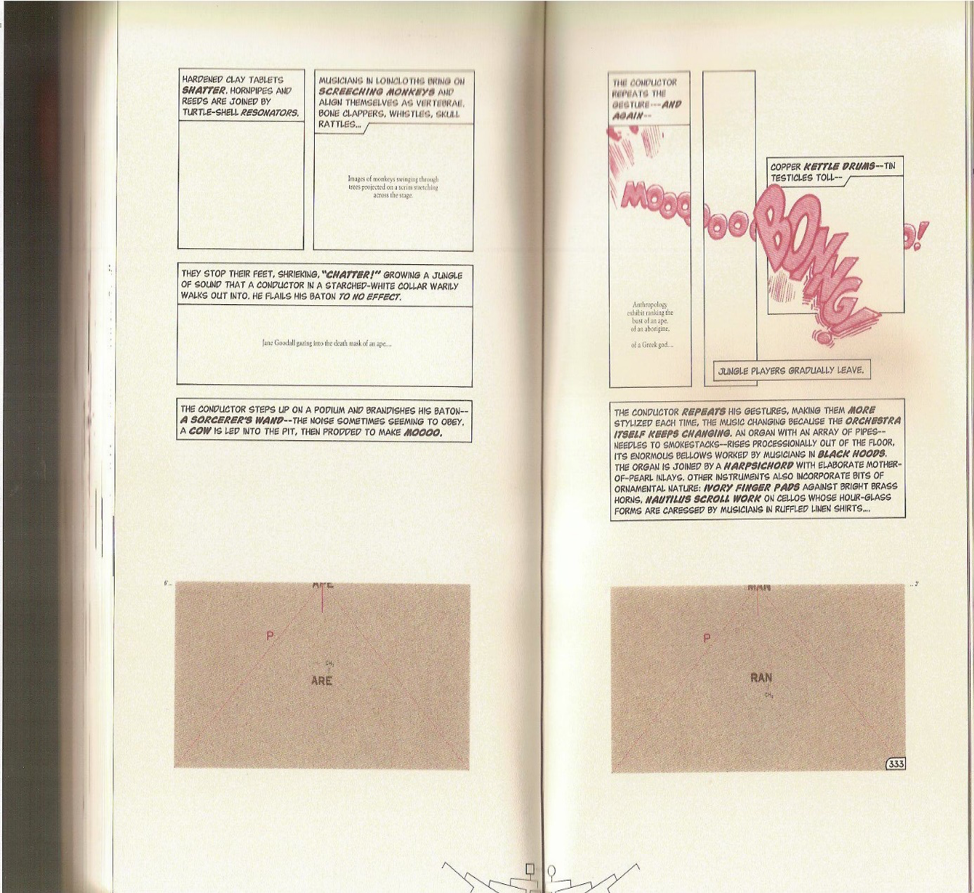

A Sound Experience

Reading is sonorous, as the cartoon onomatopoeia reminds us. More largely the play on repetition creates musical patterns that set the text into motion, as the return of given sounds and rhythmic structures brings back their previous occurrences into the reader’s mind and ears. Among the often recurring words, one may notice “natural”, or “evolution” (Tomasula 2004, pp. 152-154) – of species and languages – a notion which, as is often the case in this book, is also embodied through pictures5, thus making of VAS a performative novel, which stages and enacts words such as “evolution” or “reproduction”:

Mutation is another of those recurring terms6. The mutations of the English language are encapsulated in one paragraph, aptly ended with the phrase “in other words” (Tomasula 2004, 68), the emblem of joint changes in vision and in formulation. The gerund “writing” may be an even more pervasive term: Square’s writing of his novel, what’s written on the body7, even the family cat’s tail being perceived as a “question mark (a semiotics of vertebrae)” (Tomasula 2004, 19).

Thus several musical lines are superimposed, which, together with the many voices at play, form an “Opera” indeed, “an Opera in Flatland”, a polyphony rather than a sequence of solos or even duets, and emphasizing contrasts and distance, especially through the form of irony. The marginal voices that are made to be heard in VAS in any cases bring out the scandals of History through juxtaposition:

In smaller, italic font, a fragmented sentence running over the two pages in pieces is progressively put together by the reader: “The ‘Unfit’ also including those who contributed to industrial inefficiency … and those with VD … and the civicly unrighteous … and those who gave sexual emissions … or were racially impure … or chronically drunk…”8 (Tomasula 2004, pp. 54-55)

VAS thus mocks the deviation of the democratic ideal in America, for instance by celebrating the diversity of salad dressings available in the land of free choice, which stands in sharp, ironical contrast with the bard of America’s “celebrat[ing him] self” in Leaves of Grass, quoted on page 298, which displays the famous line “I contain multitudes” in marge font. Through his song Walt Whitman in his times belched out a plea for diversity through the very forms he invented. Similarly – mutatis mutandis – in VAS the layout enacts diversity by offering its – indeed destabilizing – experience to the reader. The democratic ideal thus conveyed does not amount to singularities merging into the indistinct average mass; on the contrary, singularities and specificities are enhanced, while the reader remains free to imagine the characters’ voices and intonation (which is not the case in the companion CD, which highlights how open reading VAS is). Here the reading experience is an education in adjusting one’s voice to other voices; in life as in polyphonic singing, one can only sing one’s part with precision, finding the right volume, pitch and nuance if paying acute attention to the other voices in the piece as well as to silences, that is remaining in the constant awareness of the presence of others and of one’s (both concrete and symbolic) relation to them. Such relations, created by reading/singing VAS may be close or distant in time and space, as the book casts bridges between several cultural spheres and moments (and between, as well as through several media). Reading VAS disrupts our relation to space and time – the conditions of reading – as well as to the book.

Disrupting the Reader’s Relation to Space and Time

Far from being limited to one nor to a given number of locations and times, VAS puts the present moment of Western culture into perspective9 by encompassing the history of humankind – plus a few other species – all around the world, as exemplified for instance on pages 66–67, on page 3 of this paper). Forms of representation are thus shown to belong to a given place and time, their effects changing constantly depending on where and when they are perceived, as illustrated by an 1822 plate of “The Artist in His Museum”: “Charles Willson Peale’s art gallery metamorphos[ing] into the first museum of natural history” (Tomasula 2004, pp. 328–329); or again at the very end of the novel Square remarks how ancient science treatises are now only read “as literature” (365): is that the destiny of all texts, or a way in which all texts may be read? The careful examination of close-reading rather than cursory speed-reading? The formal qualities of VAS bring the reader to pay attention to forms and details, thus conveying a praise of the accessory, the all-but visible, which may carry the gist of the work. Some of the leitmotifs in the book – such as “often unawares”, “mostly unnoticed” – , playing on the same repetition principle as propaganda, launch a vigorous call to vigilance. While her eyes are drawn towards details, the reader is thus prompted to try to read what is actually there under her eyes rather than what she expects10.

Daniel Arasse, in On n’y voit rien, insists on the potentially damaging effects of knowledge, through the example of an art critic finding himself before Bruegel’s Adoration of the Magi at the National Gallery: “First … he recognized what he knew. As always. It had even become boring. He could no longer manage to be surprised”11 (Boucheron 2012, 25). How to conciliate surprise with knowledge and studying? Following Whitman’s invitation in “Song of Myself”, “Creeds and schools in abeyance / Retiring back a while sufficed at what they are, but never forgotten” (1990, ll. 10-11, p. 29) (“Song of Myself”, stanza I, emphasis mine)12, VAS encourages its readers to come to the work as free of prejudice as possible – and in the full array of their experience, not limiting themselves to a single frame of reading nor to one given school of criticism. VAS makes up an impressive sum of knowledge, encyclopaedic almost, as hinted at by the thumb cut-outs marking its pages, bearing the first four or three letters of the last name of a quoted author on that page (for instance “DARW” (Tomasula 2004, 189)), working as an index of sorts. But the sources are so many, and the forms of representation so varied, that the conjured up knowledge exposes its liability to obsolescence, lying as it does under constant risk of being invalidated. The contrasted notions put forward by Roland Barthes in La Chambre claire (2002) about our apprehension of photography may help clarify the response called upon by VAS. The reader should consider the book with “studium”, or application, and a general cultural interest, but let the “punctum” come into play, by being receptive to it. The punctum, that does not come from the subject but from the picture itself13, “comes to break (or accentuate) the studium”14, while also referring to the idea of punctuation, the punctum having as its specific temporality to break a continuum. Moreover, photos with punctum are likely to go beyond themselves as photographs, in the cancellation of the medium15.

In VAS too, all the media involved become more, or at least other than themselves, according to “a global effect of dispositio, allowing to build a new context from the heterogeneity of the gathered fragments”, as explained by Olivier Quintyn about collage, in his study Dispositifs / Dislocations (Quintyn 2007, 24). VAS indeed seems to constitute an apparatus, or ‘dispositif’ according to Quintyn, relying upon a logic implying that “there is no such thing as one and only true world, but several modes of constructing simultaneous, conflicting possible worlds, which only one or several effects of dispositio […] may articulate” (Quintyn 2007, 25). It may be helpful to specify that said simultaneous worlds may come to be articulated into a global functioning but without any return to unity.

The patents, the emblems of trade and property, erase the text, which might have been viewed only as a competition of sorts, between commerce and culture, if the patents did not readily turn into beautiful objects, colored butterflies flitting over the pages, offering themselves to an aesthetic appreciation, and not only an intellectual one.

VAS offers a cognitive paradigm for constituting meaning out of discontinuous percepts (Quintyn 2007, 28), forcing a new distribution of aesthetic categories and offering itself as a model for dealing with a world pervaded by proliferating signs. Setting its dispositio against, or as an answer to, the social dispositio as defined by Foucault, a complex social apparatus defined by interactions between elements of power, knowledge and discourse (Quintyn 2007, 26), VAS offers a political model in addition to a social and cognitive one.

Against the ideal of control set up by Western societies, relying on anticipation and prevision, VAS lets the unpredictable grow by playing on the reader’s expectations, while the spatial and temporal conditions of reading are being revisited. This is achieved for instance by working on clichés. On reading “Survival of?” with a question mark, the reader immediately supplies the missing “fittest”, thus herself formulating the very ideology that is being questioned. Tomasula’s use of clichés, while facing the reader with her responsibility, brings to the fore the largely automatic nature of reading, submitting language to a form of immediate capture usually reserved to images. It all goes to suggest that images as much as texts require time for one to take them in16. VAS endeavors to disrupt the conventional reading pace, mostly through the diversity of media, bringing about constant shifts in the rhythms of apprehension of the book.

While remaining an enterprise in clarifying, promoting the readers’ awareness of the strategies of representation and their possible motivations, VAS also is an enterprise of blurring, forcing upon its readers a lesson in slowness, itself an act of resistance to the race to produce and consume underpinned by high-tech. The reader is thus offered to “take the time of discerning, of measure. Such is precisely the time offered by the text through the creation of a hiatus in which competing temporalities converge,” a phrase borrowed from Karim Daanoune’s analysis of the event in Don DeLillo’s fiction (2021, 217). Thus does VAS open an intermediary, and intermedial space in which genuine experience becomes possible again – genuine insofar as its outcome is not known beforehand. Then and there it may become possible to go beyond what we have been taught to expect from a book and to actually encounter it, in an “entretemps”, an in-between times, as described by Patrick Boucheron (in L’Entretemps, one of his essays on History) (2012). Is that the third dimension discovered by Square in VAS, while his forerunner, in Edwin Abbott’s Flatland: A Romance of many Dimensions (1884), discovered volume after the flatness of the geometrical plane? Is that Homi Bhabha’s “third space”, born out of hybridity, which invalidates dual forms of thinking, while striving for the true meaning of a culture that is constantly being built? The structures in VAS indeed rely upon such non hierarchized differences and renewed translations of the original as defined by Bhabha. What both Square in VAS and in Abbott’s Flatland access is wonder.

Indeed as they look at their familiar environment – or at their own body, in Square’s case – as though for the first time, it opens to new possibilities – according to processes brilliantly theorized by Tony Tanner in The Reign of Wonder (1965). Concurrently to analysis and exposure, VAS pursues a defamiliarizing course, mainly through repetition and shifting scales, from the largest to the smallest. By dint of watching so closely, the reader may come to see new spaces open out, new objects emerging from the familiar surfaces that had been eroded by habit – in the book, and around herself.

This is suggested for instance by the palimpsest-like motif on the right hand-side page, reproducing a page very similar to most pages in VAS, with their vertical parallel lines, and that seems to cover the larger page it has as a background – hiding for instance the vertical red lines. Yet it is not quite a palimpsest since the line centered at mid-height on both pages, and reading, from left to right, “It’s sort of like whether or not you believe a flower changes color when you put out the lights” (Tomasula 2004, pp. 272-273), actually runs from the alleged background page over to the one that is supposed to have been superimposed upon it, blurring the sense of depths and more generally of geometrical structure, Eischer-like, in a way. This double page alone contains no end of surprises to whom is willing to devote the time; for instance, the central sentence may first escape the reader’s attention, in a fashion similar to Poe’s “Purloined Letter”, too obviously set before all eyes.

By inviting the readers to deviate from conventions so as to welcome surprises, and by so doing, welcome the other rather than look for imitations of ourselves,VAS opens out the possibility of ethics, together with the possibility of politics:17“ … the political may be uttered wherever it has not been instituted, in the spacing-out of measured transgressions, or of the play on norms as well as on the in-between time of evasive discourse…” (Boucheron 2012, 93). One of the political moves achieved in VAS is to displace / disrupt the book as the emblem of erudition, by bringing into it several fields of knowledge and experience, as well as by going beyond the distinction between lower and higher culture, as suggested by the cartoon aesthetics, or earlier, of the aesthetics of a children’s game – the “Science Rocks” (Tomasula 2004, 26) kit of home experiments given to Oval as a Christmas present.

The relations between cultures – or between parts of a same culture – , it seems, are no longer so much thought of in terms of trading or exchange as of deviation and piracy18, as Tomasula encourages the writing of a “corsair” history, that would “space time out” (“espacer le temps” writes Boucheron 35) rather than view it in a linear fashion, supervised by a dominant – sometimes domineering – viewpoint. This may be suggested for instance by the “Pedestrian story” inserted within the story, on five flesh-colored right hand-side pages, offering an alternative story, or possibly the story of evolution in reverse as the narrator having to abandon his car in a traffic jam discovers walking – hence the title, “Pedestrian story” (Tomasula 2004, pp. 149-159). Or is it just, as written on one of the pages opposite, a way “Of stepping out of your diorama and looking back at what you assume to be natural.”? (Tomasula 2004, 158)

Tomasula animates the book the better to desacralize it by showing the mutability of knowledge. The dissection episode in VAS is a case in point:

He studied the confusion before him, a mass of sea-slug slippery shapes. The body was so clear in the book. […] In the flesh it was so different – all snot and oysters – that he began to think that the drawings had no more relation to real bodies than medieval models of the cosmos had to actual stars. […] he remembered trying to identify constellations by comparing dots on a chart to a sky –full of uncharted stars so that seeing the constellations, mentally connecting the dots the chart said to connect, was more of a matter of not seeing than seeing – of ignoring patterns that the makers of star charts said were not there in order to see the ones they claimed were (Tomasula 2004, pp. 166-167).

The book no longer is a model against which to check the real: VAS is the real, changing, and offering itself to experience.

Conclusion

We need to learn to see and to read again, and possibly so with each book, as VAS demonstrates that reading is not a systematic practice or shouldn’t be. The reader cannot remain outside the book but is absorbed into a highly sensory experience, and this not only because of the artistic design in VAS; even ideas may be perceived through the senses, “The point being that culture came after bodies” (Tomasula 2004, 247). This may make Tomasula heir to the metaphysical poets, writing before the “dissociation of sensibility” deplored by T.S Eliot.

VAS is a performative novel that modifies its reader’s sensibility, which may be the ultimate criterion allowing to identify a work of art. VAS does so by “reveal[ing] untold histories”, a faculty ironically attributed to statistics in the novel; “untold histories” because forgotten or yet to come; or again “untold” because they may be conveyed by other means than words. Confronting several modalities of speech19 and more largely of representation highlights their ways and means of action – allowing to show language at work and at play while it remains impossible to talk about language, as Wittgenstein reminds us.

The changed relation to the book thus made possible, with its slower pace, lets words come out of the page in the full force of their mystery. Such may be one of the main powers of this book upon its reader, who comes to: “slow the reading pace so as to give all leeway to the strangeness of words, let their oddities unfold and their stridency resonate; learn not to identify nor recognize them straight away, thus neutralizing them in a deceptive familiarity; but on the contrary bring them back to the poetic brilliance and political force of their novelty”20 (Boucheron 2012, 68, my translation).

VAS reminds us of what literature can do and of what we can do with words and books.

Bibliography

Barthes, Roland. 2002. « La Chambre Claire ». In Œuvres complètes V, 1977-1980. Paris: Seuil.

Boucheron, Patrick. 2012. L’entretemps, Conversations sur l’histoire. Paris: Éditions Verdier.

Daanoune, Karim. 2021. Don DeLillo. L’écriture et l’évènement. Paris: Presses Université Paris-Sorbonne.

Quintyn, Olivier. 2007. Dispositifs/Dislocations. Marseille: Al Dante.

Tanner, Tony. 1965. The Reign of Wonder. Naivety and Reality in American Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tomasula, Steve. 2004. Vas: An Opera in Flatland. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Whitman, Walt. 1990. Leaves of Grass. New York: Oxford University Press.

Assimilations abound between the elements of language and those of the body: “sentences coagulating into cells on pages” (Tomasula 2004, 51), or again about genetic manipulations: “Composing a body as if it were a crossword puzzle was natural for Oval” (2004, 79).↩

And it is met by Square’s resistance along the same metaphorical lines: “And even if Square was his materials, it wasn’t like he was going to rewrite them” (Tomasula 2004, 312).↩

Such is the aim set to philosophy by Wittgenstein.↩

The vertical lines are sometimes used as a gradation scale, from page 61 to 69, to indicate classifications of species through what looks like a barcode – as science meets commerce, which happens often in the novel. This is but one example of the many possible interpretations even of the simplest sign, such as a line.↩

The evolving drawing on page 30 is a case in point, suggesting a kinship between all animal species and man, through the progression, from right to left, from a fish seen in profile, to a bird, a dog and finally the successive stages in man’s evolution.↩

One of the many examples of writing on the body is to be found at the very beginning of the novel: “… it was ‘His turn.’ She didn’t need to write a story for him to know she had taken hers – it was written in wrinkles from worry over counselling sessions when she couldn’t get pregnant. It was written in a tiredness from lack of sleep … It was written in microscopic fonts – the shadows of X-rays on fallopian tubes – …” (2004, 14).↩

Comments between parentheses may also expose some social ill, often enough due to the excesses of consumer society: for instance the formula “synthetic emotion (a.k.a. Prosac)” (2004, 298) exposes the far-reaching effects of the widely distributed medicine, so widely as to have become a cultural icon.↩

As has been done by François Jullien, Patrick Boucheron or again François Laplantine, to name but a few.↩

To find what one expects may be likened to finding oneself, “coated in one’s unchallenged certainties” as Patrick Boucheron has it: “l’essentiel est d’y retrouver ce que l’on attendait et d’ainsi s’y retrouver soi-même, bardé de certitudes inentamées.” (2012, 67, my translation)↩

“D’abord, quand il a vu à la National Gallery de Londres L’Adoration des Mages de Bruegel, il a reconnu ce qu’il savait. Comme toujours. À la longue, c’en était même devenu lassant. Il n’arrivait plus à être surpris. Il avait tellement regardé, tellement appris à reconnaître, classer, situer, qu’il faisait tout cela très vite, sans plaisir, comme une vérification narcissique de son savoir.” (Boucheron 2012, 25)↩

Whitman’s presence is felt in VAS on several occasions, for instance through the famous line “I contain multitudes” (2004, 298).↩

Le studium est “traversé, fouetté, zébré par un détail (punctum) qui m’attire ou me blesse.” (Barthes 2002, 819)↩

Le punctum “vient casser (ou scander) le studium.” (Barthes 2002, 809)↩

The expansive power of punctum brings the photograph to cancel itself as medium, so that it seems no longer to be a sign, but the thing itself. (Barthes 2002, 823)↩

While the common view is that hearing is primarily temporal, vision primarily spatial, VAS reminds us that vision is temporal too.↩

“… le politique peut s’énoncer partout où il n’est pas institué, dans l’espacement des transgressions mesurées, du jeu des normes et de l’entretemps d’une parole évasive…” (Boucheron 2012, 93)↩

“Reste que les circulations culturelles ne sont pas des transferts de fonds, que les concepts se trafiquent davantage qu’ils s’échangent et qu’ils se piratent bien plus qu’ils se monnayent.” (Boucheron 2012, 35)↩

For instance through the ironical question, “Has anyone seen an ionic bond?” (Tomasula 2004, 52) which highlights gaps in scales, time periods, and fields of experience as well as between the languages used to describe or refer to them.↩

“Ralentir l’allure pour laisser faire l’étrangeté des mots, les laisser installer leur bizarrerie, faire entendre leurs stridences, apprendre à ne pas d’emblée les identifier et les reconnaître pour les neutraliser dans une fausse familiarité, mais au contraire leur rendre l’éclat poétique et la force politique de leur nouveauté.” (Boucheron 2012, 68)↩