The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals a goose from of the common,

But leaves the greater villain loose

Who steals the common from the goose.

-Popular poem from the 17th century, cited in (Boyle 2003, 33)

Introduction

Boyle (2002) and Marcuse (2009) start their articles with the above verse of a traditional English jingle, to criticize the double standards of law and to express that injustice structurally lies in the role of power. Centuries after the verse was first sung, it is relevant within the context of policies which aim at privatizing public resources, while impeding the civic society groups from managing them. Nevertheless, these policies are not the one and only case. Policies are formulated in various locations and scales, influenced by a variety of variables, and several examples of coalition between states and civic groups occur. In this paper, a case of such a coalition is examined through the lens of the urban commons and within the urban planning “arena”, as planning has become “a political space that continuously develops through top-down/bottom-up dialectic conflicts” (Tulumello, Cotella, and Othengrafen 2020). The case examined is the former military camp Karatasiou in Thessaloniki, which is a site contested by the citizens and the municipal authorities as a green space, and by the central government as a space for privatization and development.

Following the threefold perception of commons (Bollier 2012); in our case study, the common resource is the land of the abandoned military camp, the community is a network of associations and informal groups that became active on the site, and the practices are the groups’ actions and rules for the using, managing and claiming of the site. We focus on one of these groups, namely the PerKa cultivators. Through the utilization of information from interviews with members of the group, older and local press articles, we attempt to present the historical framework regarding the groups’ claims for this area and their relationship with the local authorities. The purpose is to showcase the importance of urban commons in the planning process and their potential to prevent privatization and to explore the relationship between urban commons and the “partner state”.

The paper is structured into the following main sections:

- In Section 1, the context of current policies and planning is presented, which consists of a “background” for the case study.

- In Section 2, we present our interpretation of the concepts used, and the relevant literature around the main concerns of the paper.

- Section 3, 4 and 5 are respectively an analysis of the site, the history of claiming it, and the initiative of PerKa.

Current policies and planning deregulation

Tulumello et al.’s (2020) research on planning reforms in Portugal, Spain, Italy and Greece, shows that amid crisis and austerity, European Institutions have used the conditionalities attached to bailout packages as an instrument of pressure to frame what can be considered an “implicit Southern European spatial planning policy”. This policy included the testing and implementation of spatial planning and territorial governance reforms that deepen neoliberal governance. There was a “homogenization” of legal planning frameworks: new planning laws have in common the simplification of procedures for land-use change and spatial intervention in exception to regulations, as well as the acceleration of procedures for public works. Furthermore, they show that spatial planning in Southern European countries has become a political space that is continuously developing through top-down/bottom-up dialectic conflicts. These findings are more than evident in the case of open public spaces. Research on politics for public space in a broad range of European cities concludes that inclusive governance for the public space “is a possibility, but apparently only after resorting to resistance, protest and conflict, which has forced the others to listen and take into account the voices that had remained unheard” (Madanipour, Knierbein, and Degros 2014, 134). In other words, public space is contested and needs to be fought for.

Within the aforementioned South European planning policy reform, planning practice and legislative framework in Greece has focused on attracting direct foreign investments by privatizing big parcels of public property. One can have a look at the webpage of the Hellenic Republic Asset Development Fund (HRADF) to see that public property of various sizes, locations and uses, varying from a single building to a whole beach, port or airport is being sold for “development purposes”. Confirming Tulumello et al. (2020), in Greece the spatial planning reform came center stage with the Law 4024/2012 which, among other things, included the approval of the Memorandum of Understanding on the Specific Economic Policy Conditions, known in Greece as the “Second Memorandum”. This memorandum and specifically subchapter 4.2, entitled “Improving the Business Environment and Enhancing Competition in the Open Markets”, included the action entitled “Planning Reform” according to which:

the Government reviews and amends general planning and land-use legislation ensuring more flexibility in land development for private investment and the simplification and acceleration of land-use plans. (Giannakourou and Kafkalas 2014, 518)

Following this direction, a series of legislative acts reformed spatial planning policy. Planning procedures became more “favorable” to investments and the market’s needs towards a more flexible and neoliberal approach (Papageorgiou 2017). Three different legal frameworks for urban and regional planning (L. 4269/2014, 4447/2016 and 4759/2020) were voted over a short period of 6 years. The last voted planning framework (L. 4759/2020) does not have a single passage mentioning public participation, even though previous planning frameworks–and especially L. 1337/1983–did. Among others, the new frameworks for planning introduced a new planning instrument called “Special Spatial Plan” (Eidiko Choriko Schedio), which was later renamed to “Special Urban Plan”–Eidiko Poleodomiko Schedio–(L. 4759/2020).

[This instrument is introduced] for the spatial organization and development of areas regardless of administrative boundaries, which can function as receptors for plans, projects and programs of supra-local scale or strategic importance, for which special regulation of land uses and other development conditions are required. (Government Gazette 2020)

What is really special about this plan, is that it can include settings for all issues regulated by the former plans of an area and it can modify these settings (Government Gazette 2020). Practically, this means that if an area has development limitations by the statutory plans (in terms of land uses, building-plot ratio, maximum building heights, etc.) these limitations can be overcome if the project is “of supra-local scale or strategic importance”. While the criteria of what is “of supra-local scale or strategic importance” are not defined, it is obvious that small scale enterprises and poor individuals are excluded, and corporate giants are included. Furthermore, according to article 8 par. 3 of the same law, “if the initiating body of the Special Urban Planning process is the owner of the area to be developed, the publicity process […] is omitted.” This publicity process was legislated in 1923, and it refers to the right of the citizens to be informed and to object to the urban design of a site. The only chance left for public or private bodies or citizens to express their opinion in these planning processes, before appealing to the courts, is the consultation process of the Strategic Environmental Impact Assessment of the Special Urban Plan, which is compulsory for the state, because of the EU Directives (2003/35/EC and 2011/92/EU). Finally, according to the recently voted new framework of spatial planning (L. 4759/2020, article 95 par. 3) the Ministry of Environment and Energy will create a “Register of Certified Spatial Assessors” (i.e. companies or individuals). The Ministry will be able to assign to these assessors the whole work around urban and regional planning and urban design studies, which is now undertaken by the public sector.

In short, the planning deregulation in Greece (2014-today) has undermined the role of the citizens and the role of the public sector, and reduced environmental or social restrictions that would possibly delay, postpone, or cancel major private investments. Nevertheless, it is already noted that this shift towards a more flexible and neoliberal approach did not achieve economic growth and the state’s requisite economic goals (Papageorgiou 2017).

These new policies affect the former military camps, which are viewed by the central government as parcels of land for privatization and development. Since the 1980s’, the removal of camps from inner urban areas has been an intent of planning authorities, and a wide range of scholarly studies has focused on the use of the former military camps, most often considering them as “a last chance to increase public green spaces” (Athanassiou 2017). The removal of the camps from the urban areas is institutionally covered by L. 2745/1999. According to this law a Service for the Utilization and Relocation of Camps is created, but it operates with market-oriented criteria and belongs to the Ministry of National Defense. Nevertheless, the law recognizes that the existing military bases in the camps are not compatible with the uses that surround them and that their removal can be valuable for the creation of green spaces, recreation and social infrastructure. A portion of the area to be released could have uses with a potential for financial performance, in order to finance the relocation cost of the camps. This law was never implemented in the case of Thessaloniki former military camps. A new statute, L. 3883/2010, described that the properties owned by the National Defense Fund (including all military camps) can be granted to local authorities free of charge if reasons of general interest are served.

Urban commons and the planning process

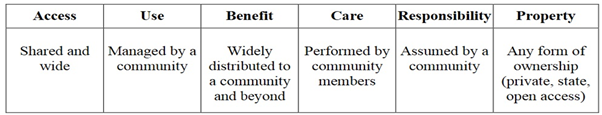

In this paper, we follow the threefold definition of commons, i.e. a concept comprised of collective resources, institutions/practices/rules for regulating those resources, and the community that devises the institutions (Bollier 2012; Dellenbaugh et al. 2015; Huron 2017). After Ostrom’s (1990) initial success in addressing the “tragedy of the commons”, a broad and diverse “commons literature” has emerged and the notion of the commons gradually shifted. Contemporary authors perceive commons not only as a resource shared by all members of a community, but mostly as a broader concept involving certain social practices. Linebaugh (2008) was the first to state that “to speak of the commons as if it were a natural resource is misleading” and focused on “Commons as verb” or “commoning”. Following this idea, Gibson-Graham et al. (2013) characterize commoning as “a relational process–or more often a struggle–of negotiating access, use, benefit, care and responsibility” of a resource. This process is applicable to any form of property, whether private, state-owned, or open access. Ignoring property rights, but focusing on social processes, Ostrom’s approach of commoning is suitable for examining the creation of commons in private urban areas within cities, where public land is sparse, and for studying areas where property rights are contested, like the urban void of our case study.

The term commons today implies a third path (for governing resources and for social/economic/political organization) “beyond the markets and states” (Ostrom 2009; De Angelis and Stavrides 2010; Bollier and Helfrich 2012). Nevertheless, it has been pointed out that the role of the state towards the commons is of critical importance for enabling and empowering the commons. Bauwens and Kostakis describe the role of the “partner state approach” (PSA), in which:

the state enables autonomous social production. The PSA could be considered a cluster of policies and ideas whose fundamental mission is to empower direct social-value creation, and to focus on the protection of the commons sphere, as well as on the promotion of sustainable models of entrepreneurship and participatory politics. (2015, 2)

Planning literature about commons binds the terms planning and commons in two ways. The one is planning for the commons (Popper and Popper 1987; Vogel 2017; Brinkley 2020), which means that official planning today should enhance them, and it shares similarities with the PSA. The other is planning by the commons, which means that the commons as social spaces can produce grassroots or informal planning (Porter et al. 2011; Eizenberg 2012; Delsante and Bertolino 2017), or even play an essential role as a stakeholder in official planning (Gerber et al. 2011; Müller 2015). These two ways of binding the terms are closely interrelated. An official plan promoting the commons, even as mere material spaces, would strengthen their role as stakeholders and vice versa, the commons creating informal or grassroots planning can press official planning practice for their own recognition (Seitanidis and Gritzas 2022).

In our case, it is important to mention the relationship between participatory planning and urban commons. Commons are considered as both a primary source and an output of DiY Urbanism (Volont 2019) and as practices of “open source urbanism” (Bradley 2015). The process of commoning is viewed as an answer to the absence of a participatory culture within a state (Ortiz 2015) and as an effort to disrupt official planning procedures: an active counterpart to state and market actors on an urban platform (Müller 2015). On the other hand, urban commons are also capable of becoming “bottom-up” initiators for and within urban participatory planning processes. Müller (2015, 159–60) studied the case of Gleisdreieck Park in Berlin and highlighted this potential:

- Urban commons can be regarded as an indicator showing the actual necessities of certain groups of city dwellers.

- Governments and urban planners can have an advantage if they perceive urban commons as serious partners, as they can freely gather ideas and expertise, because the participation of the commoners is not motivated by profit. Allying the commons also means avoiding civil protests, which might spoil the development process.

- Commoners show an increased level of identification and responsibility with the object/resource. So they are more likely to continue taking care of their resource/neighborhood/park even after the completion of the planning process, relieving state or local authorities.

- Referring to the “collaborating” and “empowering” level of public participation, urban commons could be more adequate partners than the “general public”. Urban commons have already developed common visions and requirements and could be able to bring the necessary collective power along to take an active political role.

The potential of commons to deal with the privatization or “enclosure” of common resources is also relevant to the planning process, as this is directly linked to the land uses of material space. Enclosure is an old and continuing issue–firstly detailed by Marx in Capital (1999)–and currently used by a wide range of authors, who pointed out the privatization of common pool resources, as an expression or a necessity of current neoliberal policies. Mattei (2013) showcases how the Italian commons movement “beni comuni” managed to “interrupt the path of neoliberal constitutional transformation” as the movement induced referendums that abolished a series of statutes recently voted by the Parliament. In a broader context, urban commons counteract to “a process of the continuous enclosure of popular sovereignty” (Bailey and Mattei 2013). Mattei (2013) views the “beni comuni” as a form of Italian Occupy movement, and similar to this point of view, Delsante and Bertolino (2017) describe how urban commons occupied Galfa Tower, an abandoned private property in Milan. Through weekly assemblies, they developed a proposal for spatial planning to the Municipal Authorities, which focused on the community-led re-appropriation of vacant urban spaces as commons and their official designation as such by the authorities.

The site of the former military camp Karatasiou

Karatasiou former military camp has a total area of 68.9ha, and it is located in the Municipal Division of Efkarpia in the Pavlos Melas Municipality, in the north part of the Urban Agglomeration of Thessaloniki. This agglomeration consists of seven municipalities and has a population of around 780,000 inhabitants (2011 census of the National Statistics Service of Greece). It is a densely built urban area, with a remarkably low ratio of 2.7m2 of green open space per habitant1, while the international recommended standard is 9m22. The site of the former military camp is situated in an advantageous location in terms of accessibility, as it is surrounded by three highways: the Thessaloniki Ring Road, the Egnatia Highway, which connects the city with the east and west parts of northern Greece and Lagadas Avenue, which connects the city center with the areas north of Thessaloniki.

Furthermore, the site borders on amenities (two hospitals of metropolitan importance and a football stadium) and along the south border of the site, runs the Xiropotamos stream, the only stream which passes from the urban agglomeration having water throughout the whole year. Finally, there is an archaeological area next to the site, the Byzantine Watermills. All the above make the site an attractive area for developers. At the same time, the lack of open green spaces in a densely built city, make it claimed as a green area by the citizens. Inside the site, there are pine trees, low vegetation, abandoned military buildings, asphalt roads formerly serving the military camp, a playground and a small football ground and small farming plots created by the PerKa initiative.

Karatasiou timeline

The original area used by the military was 134ha. During the period 1950-2008, parts of the area were conceded for the construction of the nearby hospitals and freeways. As a result, 68ha remained when the former Karatassiou camp was abandoned by the troops in 2003. In October 2005, following relevant requests, the General Directorate of Infrastructure of the Army agreed to concede 12ha out of the 68ha to the municipal authorities to implement a housing program for public needs in the existing buildings of the camp. This agreement was never official, because the proprietorship of the space was contested by the Ministry of Economics. However, in 2006, the Municipality implemented projects on the site by designing a playground, renovating and equipping an existing building on the concession area (intended to be used as a canteen) and constructing outdoor sports infrastructure and municipal lighting throughout the concession area.

In 2007, an informal group of local residents formed the “Citizens’ Movement for the Karatassiou Camp”, which undertook a series of actions to claim the public use of the whole site. This movement, in collaboration with two teachers, who were active in the “Environmental Thematic Network”, and the network “Active citizen in the municipality of Pavlos Melas” began efforts to mobilize citizens to claim the space. In an open event that took place in the 2nd Technical High School of Stavroupolis, a questionnaire was promoted by students to showcase the will of the inhabitants to use the site as a park. These efforts gradually gained prominence, and at that time a wider debate began to be unlocked about the potential of the former military camps in the urban fabric. In this way, there was a tendency for cooperation of different bodies of the city to jointly deal with this issue. As a local elected official interviewee stated, “it is worth mentioning that for Karatasiou there was no state support in the beginning and, unlike other former military camps, all efforts started from the bottom”.

In 2008, the actions of the “Citizens’ Movement for the Karatassiou Camp” involved an effort to mobilize the Municipal Council for action such as setting up a committee of all political parties, collecting signatures, sending letters, etc. Later in 2008, the movement also participated in the co-creation of an informal coalition called “Thessaloniki Network of Movements”, consisting of around 30 collectives and organizations from all over the city. The aim of the coalition was to provide all these actions with both legal and protest-oriented support. Thus, a set of bodies began to be built that had as a common goal the claim of public space in a wider way and this indirectly concerned Karatassiou as well. In the same year, the municipality granted 300m2 for cultivation in the informal group “environmental team” of the 2nd High School of Stavroupolis, inside the former camp. Thus, new permanent activities of the citizens emerge into the contested area. The “Citizens’ Movement for the Karatassiou Camp” co-organized presentations with the municipality (Apr. 14, 2008), workshops (Nov. 14, 2008; Feb. 2, 2010; Sep. 6, 2010), tree planting (Dec. 7, 2008) hiking (May 10, 2009) and other cultural and educational activities within the camp to raise the awareness of the residents and with the assistance of other citizens’ associations and schools of the surrounding the area (Sep. 28, 2009; Sep. 3-5, 2010).

In 2009, Citizens’ Movement merged with a parallel initiative, the “Karatasiou Voluntary Group”, and obtained an institutional form, the “Karatasiou Cultural Association”. It has about 200 members, mainly residents of the areas around the former camp. The purpose of the association is to claim the camp area as a place of green, recreation and culture through environmental awareness, educational, informational and entertainment activities. The same year, there was a clash between the locals, members of Karatasiou Cultural Association, joint military, and police forces during an attempt to plant trees in the area. On the one hand, the Association had the support of the majority of the local community, and on the other hand, the army and the police exerted legal pressure on those present, asking their reason for being there and demanding identification papers. This event had a positive ending for the Association, thanks to the mass popular support. A few months later, a hiking action called “We run for the camps” took place. It was an initiative of “Karatasiou Cultural Association” and the “Thessaloniki Network of Movements”, and it was jointly organized by these groups and the Municipalities of western Thessaloniki.

During the period 2010-2011, there was a successful effort to mobilize other associations in the area, such as the Union of Pontians of Polichni, but also sports and cultural clubs, which began to be more actively involved in the former camp, through their own activities (dancing, sports, etc.) and through volunteering for taking care of the space. Since 2010, Karatasiou Cultural Association has been annually organizing cultural events entitled “Reviving Karatasiou”, with the active participation of the association “Union of Pontians of Polichni”, and the support of the Municipality of Pavlos Melas.

In May 2011, amidst austerity measures and economic crisis, a part of the abandoned military encampment started being farmed by an ad hoc group of citizens called PerKa abbreviation for Periastikoi Kalliergities, which literary means “Peri-urban Cultivators”.

In May 2012, Pavlos Melas Municipality approved (Municipal Decision 298/2012/24-5-2012) the preliminary proposal of the Urban Plan of Efkarpia, the municipal subdivision where the former military camp is located. This plan needs further approvals to gain statutory status. The Urban Plan and the Municipal Decision determined that at least 75% of the former camp will be green area (metropolitan park) and the rest of the site will host public amenities. According to this plan, housing, retail, hotels, commercial uses, etc., will not be allowed on the site.

On August 27, 2012, during the “Reviving Karatasiou” event, military tanks of the 3rd Support Brigade, based in the Papakyriazi military camp in the nearby municipality of Evosmos, and other military vehicles entered the streets of the former camp. The citizens and the municipality reacted, and the official reply of the army was that the vehicles were technically tested for their proper operation. In October 2012, the Ministry of National Defense canceled the (unofficial) agreement with the municipality, and lifted the concession it made in 2005, saying that the municipality did not comply with the agreement. The Ministry of National Defense asked the municipality to stop taking actions on the former camp and designated the municipal authorities as a trespasser.

The following year, more specifically in March 2013, the army placed a lock and warning signs at the entrance of the camp. Essentially, there was control over the entrance inside the area. Police officers, accompanied by the army officers, entered the site and certified the identities of the visitors putting pressure on them, especially on the members of PerKa, as all of them were considered intruders of the area. Within hours, a significant mass of the local community, collectives and organizations, as well as the press, attended. Authorities withdrew from the area and a legal dispute ensued, as citizens (led by “Thessaloniki Network of Movements”) filed a lawsuit with the Ministry of National Defense for the “invasion” of the former camp and for the controls. In this way, the conflict of the authorities with the local community reached its zenith, and it became widely understood that there are important interests in the state. In this unprecedented judicial action for Greece, many interviews and actions around the specific event followed, and the event gained popularity, as a multitude of questions were held in the European Parliament and in the Greek Parliament (i.e. 10 questions in the Greek Parliament for the future of the former military camps in the summer of 2013). Regarding the course of the trial, the case went to the military judges and it was archived. The citizens who filed the lawsuit were not substantially informed about the course of the trial, but only received the proceedings of the witnesses’ testimonies.

At the beginning of 2014, the “Initiative of associations and bodies for the former camps” was created (with the mobilization of the Karatasiou Cultural Association), and submitted a resolution of positions in all the municipal councils of the city in order for this text to be voted for and sent to the Prime Minister and the relevant ministries, as it was done. The resolution included requests such as:

- The lift of transferring in any way of the camps to the Fund for the Utilization of Public Private Property (HRDF), which is equivalent to be privatized for market purposes;

- The abolition of the legal framework that allows the development of the camps, i.e. L. 2745/1999;

- The broad characterization of the remarkable buildings of the camps as monuments of culture;

- The transfer of the property of the former camps to the municipalities.

The same year, the Karatasiou Cultural Association collaborated with 55 local associations and organizations, and with the assistance of the architect V. Metalinou, they initiated a grassroots planning proposal for the principles of utilization of the site, which was submitted to the State’s Real Estate Company.

Following these intense activities of 2013-2014, the local authorities in Pavlos Melas Municipality changed in the municipal elections of September 2014. Several prominent members of the struggle for claiming the former camp acquired key positions in the new local authorities. The president of the Karatasiou Cultural Association became deputy Mayor of Green Areas, another volunteer and member the Association became Director of Culture, Athletics and Voluntarism, and few years later, one of PerKa’s founding members and former spokesman, became an unwaged (but official) consultant of the Mayor. Since 2014, the Municipality has organized a series of annual events with the ultimate goal of informing, raising awareness and activating the citizens about the need to claim and use the former camp as a free space for greenery, culture, sports and recreation. Such an event is the environmental meeting of the school units of the Municipality, where the environmental groups of the schools present their annual actions. The Municipality also became patron for organizing the sports event “I run for the camps”, an annual celebration of the kindergartens of the Municipality and an annual football academy tournament being held inside the former camp. In addition, since 2019, volunteer groups that cooperate with the Civil Protection Office of the Municipality have been housed in former military buildings, to organize training exercises and first aid seminars.

In 2018, after an accusation of the Ministry of National Defense and a corresponding prosecutor’s order, two Mayors (of the periods 2011-2014 and 2014-today) were tried for encroachment, illegal occupation and use of public property, i.e. the parts of the former camp. This sparked a huge wave of reactions. A mass of collectives and citizens attended the trial. The court decided on March 8, 2018 that there is no issue of encroachment and illegal activities on the part of the municipality as long as there is ambiguity in the property regime, and the public amenities of the municipality on the site are constructed and maintained through public funds.

From May 9, 2018 to July 19, 2018, Pavlos Melas Municipality organized a broad public participation process for the urban planning/design of the former military camp, where 55 different associations/groups participated by submitting their proposals. This process led to a proposal for the conversion of the site to a metropolitan park with various amenities. The Municipal Authorities finally formulated these proposals to a text and maps approved by the Municipal Council (Municipal Decision 158/27-2-2019). A study of the proposals placed forth by the Municipality, showed that they touched common ground with the local associations’ demands (Maknea and Georgi Nerantzia Tzortzi 2019). This proposal was finally sent to the Prime Minister and other public bodies related to the utilization of the site.

In August 2019, while answering to the questions of Parliament Members for the future of the site and for the demand of the local society for its conversion to a park, the Minister of National Defense, stated that “This former camp is a high value property, which needs holistic development, with multifaceted integration of uses such as housing, work, trade, leisure” and the involvement of investors on the site is a “one-way street”.

Maknea and Georgi (2019) conducted questionnaire research to produce a bottom-up urban design of the site. In particular, they suggested some interventions, rather than a general regeneration. They argued that redesigns in the form of radical interventions, which have been proposed from time to time, would alter the physical and historical elements of the camp, thus they remained on paper because the site would be degraded as these interventions would have a negative impact on the local community. The main features of Maknea and Georgi’s (2019) proposed master plan are the integration of Xiropotamos stream, the balanced spatial performance of both urban cultivation and urban forests and the creation of a small lake that regulates the ecosystem of the site.

In October 2019, Pavlos Melas Municipality approved the final proposal of the Urban Plan of Efkarpia, and forwarded the plan to the Ministry of the Environment and Energy for its final approval in order to gain legal status.

In December 2020, the Metropolitan Planning Council of the Ministry of the Environment and Energy, approved the General Urban Plan of the Municipal Unit of Polichni, after a unanimous vote by the members. The Metropolitan Planning Council agreed with the Municipality’s Urban Planning proposal, and added a dormitory and a dining hall for students on the site. The Council’s decision determines the land uses for the future development of the former camp. Specifically, a minimum of 75% of green space is provided. The remaining 0 to 25% of the space will be used only for public amenities of metropolitan range (Cultural, Health and Education) and not for commercial purposes. The details of the area and type of public infrastructures are to be defined at a later stage of planning. It was the first important official success in the planning process on behalf of the Municipality/Movements coalition.

The Metropolitan Planning Council of the Ministry forwarded its decision along with the Urban Plan to the Legislative Department of the Ministry, to give it a Government Gazette form and to have it signed by the Minister. In July 2021, the Urban Plan took the Government Gazette form for Ministerial Decision and it was signed by the Minister and published (Government Gazette 2021). This Ministerial Decision, ratifies the land uses of green space and amenities, but, surprisingly, it states that the further implementation of the land-use plan (i.e. design and construction of the parks) in Karatasiou will require the consent of the Ministry of National Defense. Practically, this means that the plan will not be soon and easily implemented. Nevertheless, this decision can be considered a victory for the locals, because the only land-use allowed is green space and few public amenities (maximum 25% of the space) and any other type of land uses on the site related to private profit and decrease of green space (like residential, retail, leisure etc) is forbidden.

Briefly the history of claiming the site, shows that a dense network of coalitions was built between various bodies of diverse scope and legal form throughout the past 15 years. These independent groups had close cooperation with the Municipality and supported each other, “in the spirit of the new politics that seeks alliances rather than mergers” (Gibson, Graham, and Roelvink 2013, 454). These alliances did not have the form of steady contracts, but they consisted of an informal network, whose members had very regular oral communication. They co-devised and supported demonstrations, rallies and various events and actions for claiming the public use of the site. It took years of struggle and constant bottom-up attempts of urban planning/design and submitting the proposals to the various official authorities, to reach what was recently achieved.

The PerKa initiative

During the past 6 years, the initiative of PerKa attracted the attention of scholarly work, and it has been endorsed for a variety of reasons. Municipal allotment gardens in Greece are not currently incorporated in a long-term sustainable urban planning strategy, as integral parts of the city’s sustainability fabric and provide a short-term action of social policy rather than a long-term sustainable urban planning strategy challenging the conventional modes of land management and governance (Anthopoulou et al. 2017). Nevertheless, it has been mentioned that the case of PerKa highlights the potential of urban gardening initiatives to challenge planning culture towards a more democratic urban development (Nikolaidou and Sondermann 2016). PerKa is presented as an example of high interdependence between social practices in urban farming (Kontothanasis 2017), as a claim of a different daily relationship of the city with nature (Athanassiou 2015a, 218) and as an example of “active agents who claim their right to decide about the city they live in, challenging indisputable global mandates and their local materialization in the process” (Athanassiou, Kapsali, and Karagianni 2015, 9). Finally, the initiative of PerKa is also juxtaposed as a result of crisis-related hardship and an example of grassroot initiative for the city’s resilience (Snieg, Greinke, and Othengrafen 2019; Chinis, Pozoukidou, and Istoriou 2021). In this section, we explain what PerKa is and why it is viewed as an urban common and as an agent that initiated informal grassroots land use planning by changing the real use of the site and also an official stakeholder that participated in the city planning process.

The beginning of PerKa’s story is worth mentioning as it does not predispose for what followed. According to one of the interviewees who is one of the collective’s founding members, and renowned volunteer and advocate of green spaces in Thessaloniki, it was a group of few individuals that started the initiative. These individuals shared a common intention: to grow organic vegetables for their own use using traditional seeds and plants. They did not originally intend to protect the urban void from exploitative development. Food safety, environmental protection and coming into contact with the earth were their main concerns. Firstly, they came into contact with a few of the municipal authorities of the urban agglomeration of Thessaloniki, trying to find a space where they could cultivate. But the lack of available space and bureaucratic problems they faced for legitimately using an officially municipal space, turned their attention to the urban void of the former military camp Karatasiou. Apparently, it was easier for them to accomplish their goal in a legal gray zone, occupying the urban void. They collaborated with the Karatasiou Cultural Association and a total of 30 people constructed the first farm “PerKa 1” in May 2011. It consisted of two large pieces of land (100 and 200 square meters each). Soon after, individual plots of 40m2 were created for individual use. This informal community has grown to 120 members, defending the former military camp area from privatization and demanding its conversion to a green area. At present, there are seven “farming groups” PerKa 1, 2, 3, and so on, farming less than a hectare of the former military camp. As far as it concerns the action of occupation the initiative states on their website:

Not only do we not want to take over the area, but by maintaining its open spaces and buildings, we function like a temporary bridge between today’s official abandonment of the camp and the realization of a complete and integrated plan for turning the camp into a free and open green space for the citizens of the Pavlou Mela municipality, but also for the entirety of Thessaloniki, who we call to create here the next farming group, or take part in other actions supporting our common cause.

PerKa members do not elect a president or a council. Decision-making takes place on general assemblies of all the PerKa groups and sub-assemblies within each PerKa group. The first members formulated and signed a “Declaration of Principles of Cooperative Operation” which adopted values of direct democracy and ecology and can be amended only by the general assemblies of the collective. From 2011 to 2017, PerKa collective has been very active in holding assemblies. Most of them had an average of around 40 attendants and they were originally held twice a week. The “Declaration of Principles of Cooperative Operation” describes the principles, responsibilities and rules that every new member has to accept. These rules can be about the farming techniques (e.g. the use of artificial fertilizers and pesticides is not allowed for the farmers), the use of space (e.g. the construction of fences to enclose the individual plots is banned), the decision-making process, etc. As the number of farmers significantly grew, issues of not complying with the rules arose. In 2018, some new PerKa members disrespected some of the rules and insisted on creating a short dividing wall, made of concrete, around their plots. An unsolved internal conflict occurred, as the collective did not have the legal means to stop those who did not apply with the rules. Following this conflict, founding members of the collective who favor ecological values, asked the municipal authorities to intervene. Therefore, the Deputy Mayor of Green Areas (who was also former president of the Karatasiou Cultural Association) sent a letter to each member of PerKa. This letter quoted the “Declaration of Principles of Cooperative Operation” and stated that any member that will not sign it and comply with its terms within 60 days will be expelled from the site. Even though it is disputable if the municipal authorities did have the jurisdiction to expel anyone from the site, members from both sides of the argument quit Perka. Among them, several of the founding members that were at the forefront of holding general assemblies and volunteering for the causes of PerKa, who were disappointed with the situation.

PerKa engages with a variety of associations/groups/collectives: especially with the Karatasiou Cultural Association, who helped the group to establish on the site. They are part of the wider network of groups and associations campaigning for the public use of the former camp. They participated in dozens of actions that took place for claiming the site for public use and co-organized several of them. As a farming group, they cooperate with the Peliti community, a group that uses local-traditional unmodified seeds, which are threatened by extinction by corporate varieties, and they have created their own nursery.

As far as it concerns the relationship with the Pavlos Melas municipality, when PerKa was established on the site, they just informed the municipal authorities by sending them a letter justifying their action and their intentions. The Municipal authorities accepted the collective as an advocacy group working towards the common objective of protecting the public land and claiming it from the Ministry of Defense. From the very beginning of the initiative, the municipality has supplied PerKa with water, which is used sparingly according to PerKa’s principles. Within the former military camp, the cultivation value of the land was low because the soil was extremely poor in nutrients. In July 2016, the Municipality proceeded with soil remediation, replacing the poor soil with a suitable one, at a depth of 30 cm, offering an important assistance for the continuity and the spread of the PerKa initiative. All the above indicates that the Municipality followed a “partner state approach”. After the aforementioned internal conflict in 2018, the general assemblies are infrequent, practically substituted by smaller assemblies of each PerKa group, and municipal authorities have been more decisive in the management of the site. One of the interviewed members who called for the municipality’s intervention mentioned “we sacrificed part of our self-management in order to maintain our ecological values”.

Based on PerKa’s official site, participant observation and interviews, we attempt to show that PerKa initiated commoning on the site, as this concept is presented by Gibson-Graham et al. (2013), i.e. in terms of “negotiating” access, benefit, care and responsibility of the land of the former military camp, which is the common pool resource in our case.

Access: The farms are accessible to anyone at any time. Fences are constructed around each one of the farming groups and each group has one or more entrances by small handmade doors. There have been cases of stealing vegetables, but this is not often, and it does not deter the farmers, as their primary concern is not having a high production. PerKa is accessible not only as a place, but also as a productive resource. The initiative is open to new members, who are most frequently residents from the camp’s vicinity but also from other areas across the city. New members are welcomed regardless of their beliefs or social class, as long as they agree with the PerKa’s terms. Newcomers include immigrants, unemployed people, and low-income citizens stricken by the economic crisis. The initiative’s Declaration of Principles describes the process of acquiring a new plot and the way newcomers may contribute economically to the construction of it, if needed.

Benefit: The benefit (i.e. the food produced) is distributed to the members of the PerKa and beyond. According to the collective’s rules the food produced is only to be consumed by the farmers or to be given for free and it cannot be sold. The first plots of PerKa were cultivated collectively and all the production was distributed to the Social Grocery of the Municipality of Pavlos Melas, the Immigration Hang Out Place and various churches (Maknea and Georgi Nerantzia Tzortzi 2019). The idea of offering part of the production is transplanted to the majority of PerKa members, which, according to an interviewed member, is one of the reasons they are not upset when they observe few vegetables of their gardens missing. Apart from vegetables, the collective also distributes the knowledge that it accumulates and produces, by organizing training seminars–open to anyone interested–on farming and ecological building techniques.

Care: PerKa members take care of the land they cultivate, but also of the surrounding space and in most cases, they try to take care and re-use the nearby abandoned military buildings as gathering places and as storehouses for gardening tools and equipment. The process of cultivating the land was initially collective, but it soon turned into individual farming plots. During our visits in PerKa groups, we observed that each one developed its own mentality in terms of taking care of the space (e.g. in PerKa 3, they care more about their common space, and they have constructed wooden tables and chairs for common use, whereas in other groups the common space is abandoned).

Responsibility: Each member is responsible for its plot, and each group is responsible for its area. Since 2018, they are all accountable to the municipal authorities. As the collective does not have a legal form, some questions concerning responsibilities remain unanswered. The interviewees accepted that in cases of an accident (like the fall of a tree, the collapse of an old building, or a fire) there is not a mechanism which makes PerKa or its members responsible.

PerKa has been one of the most important groups active on the site, as the birth of this group marked a permanent everyday existence of citizens in the former military camp. Firstly, they changed the actual land use in a small part of the former military camp acting as agents of informal planning. This informal planning (i.e. the allocation of new PerKa groups and farming plots) was decided collectively by the PerKa General Assembly. Secondly, they made the space alive and enhanced its “publicness” (Athanassiou 2017). Additionally, the users of the space can observe the existence of ongoing human actions on the site, and this strengthens both the perceived and actual safety on the site. Thirdly, they played an active role in the process of the official planning of the site, not only by submitting their proposals for the site, but also by changing the real uses and the power relations on the site, which both have to be taken into consideration by the official planning practice. Since there is ongoing everyday human action on the site, it cannot be considered an abandoned property ready for sale. New needs and new claims for the site arose and pressed official policies and the planning process.

Conclusion

Former military camp Karatasiou is one of the many cases showing that urban voids and areas of unclear proprietary status make for hosting places off the commoning process. Nevertheless, being in a gray zone of the law, the PerKa collective was unable to resolve internal conflicts caused by disobedience, losing part of its integrity to the municipal authorities. The PerKa case shows that urban commons in Greece are in need of a legislative framework that will allow them to exist in abandoned sites. Similar cases indicate the same. In spring 2021, the occupation initiatives of the self-organized theater Empros in Athens (which has been active for a decade) and the self-organized cultural center Rosa Nera in Rethymno (which has been active for 17 years) were suddenly evacuated by the police. Within a few days, they were reoccupied by the collectives with mass public support, and as of June 2021 these clashes are ongoing and the collectives’ future is precarious. These examples, like the PerKa case, showcase the potential of the continuous struggle, but also the importance of having a legal framework to protect the urban commons, i.e. the difference between having a “partner state approach” in legislating rather than a hostile one.

The history of the former military camp Karatasiou is a never-ending struggle for public land. This struggle is contrary to current planning framework aspirations, governmental policies, state’s prerequisites for getting loans by the EU institutions and global neoliberal trends for the privatization of urban space. However, this struggle has successes. As in the case of the Italian commons (Mattei 2013), privatization is halted. A network of informal groups and associations arose and played its role in local policies, acting as a stakeholder in the planning process, as in the case of Gleisdreieck Park in Berlin (Müller 2015). Having an allied municipality, and having obtained key-positions within the municipal authorities, these groups pressed further for their claims on the site. The recent approval of the plan by the Metropolitan Planning Council of the Ministry in December 2020 has been considered the first success for the official designation of the site as a public space, and highlighted the importance of having municipal authorities with a “partner state approach”.

Despite the broader socio-economic and political contexts, new coalitions between civil societal actors and local authorities can emerge, challenging traditional state–centered forms of decision–and policy-making processes. Endorsing these coalitions should not be misinterpreted as pursuing only the partner state per se. The latter, is rather what Naomi Klein termed “a more favorable terrain” for the struggles to come (Solomon 2020), as the last verse of our opening traditional jingle implies:

The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common

And geese will still a common lack

Till they go and steal it back. - cited in (Boyle 2003, 33)

Bibliography

Source: National Chamber of Greece, 2018: (in Greek, access: 11/06/2021). Available here.↩︎

Source: UN Habitat, 2018 (access: 11/06/2021). Available here↩︎