Reactor Ciudad Vieja is an urban laboratory, guided by the research and extension group in Affective Urbanism of the Faculty of Architecture, design and urbanism of the University of the Republic, Uruguay. The objective of the laboratory is to bring urbanism closer to local processes of empowerment and co-construction of collective actions in making the city. The Pilot Program Empty Buildings of the Municipality of Montevideo, aims to: recover abandoned properties in the central and intermediate area of the city, in order to avoid their continuous expansion and contribute to the redensification and intensification of urban land use.

Introduction: an urbanism of affections and urban commons

The case study in the historic center of the city of Montevideo developed in this article shows how an urban policy for the recovery of abandoned buildings can be a means of putting these urban commons theories, as well as affective urbanism, into practice and accompanying the needs and rights platforms of local urban communities.

On a theoretical level, we state that interdisciplinary and participatory planning, used from the beginning as modus operandi of this process, has gone from the right to have an opinion and participate at the moment of designing plans and projects, to being the protagonist in the co-production of the city through platforms of social movements and citizen initiatives. This experience confirms the relevance of the internationally recognized participatory method, which includes locating oneself in a particular context, thinking habitat construction in an integrative way, starting from local histories and affections, proposing creativity in the methods to make them emerge and producing innovative results in terms of material and immaterial quality and redistribution of responsibilities in implementation and management.

“Affective urbanism” is defined as a set of practices and an epistemological framework which nurture a different idea of making a city and transforming the territory through architecture, ecology, economy, anthropology, and other fields of knowledge (Fitz and Krasny 2019; Goñi Mazzitelli and Gil-Fournier 2021; Giraldo and Toro 2020; Gabauer et al. 2022). It is an approach that questions the present dynamics of urbanization focused on the development of real estate market and private property, shifting the attention towards territorial well-being, together with environmental and social justice. This is achieved through the dimension of the emotional, that is, all that makes us protagonists of our own territories in their construction and reconstruction. These emotions and feelings have been partly studied by theoretical frameworks that focus on the social organization and “collective action” (Weber 2012; Hardin 1982; Ostrom 1990) to counter injustice and oppression. But we include the mobilization from the feeling of affection we develop for some spaces in life that refer to an identity bond, built from the past, related to being born, and having lived in the same territory. Or additionally from the present and the future, for the wish to get there and to build the optimal conditions for the best environment to live in. This is the immaterial engine that leads to search for individual, but above all, collective actions, through social organization, that this specific territory needs, as well a the actors to collaborate with, spaces to be transformed, among other actions that reinforce the well-being and sense of belonging to these neighborhoods. It is not only what we do, but how we modify and build the city around us.

We find powerful allies in the debate on participation in urban and territorial planning in contemporary social movements concerned with claiming the right to the city, a city with equal opportunities and access to services for all. On the latter, we find urban commons movements, which are sometimes different from the right to the city ones, completely in tune, as they propose a collaborative mode of work between social organizations, in order to organize and imagine ways of re-appropriation of abandoned or underused areas of the city, placing themselves between the public and the private, in the new field of the commons (Christian Laval and Pierre Dardot 2015).

The results that emerge from the case study we are going to develop onwards are encouraging: for example, the passage of looking for complementarities between groups, thanks to urban laboratories of processes, which do not put them in competition for resources, which usually happens with the traditional public calls, but rather ask them for joint projects for the allocation of funds and spaces. This meant reinforcing conflict management and decision-making methodologies through the active listening and consensus building method (Susskind and Sclavi 2011), but above all applying co-design and commoning tools (Giuseppe Micciarelli 2018) to promote associative projects in which the requirements to access the space were to be willing to work collectively to resolve aspects of material recovery, uses and activities in the property.

From the point of view of public policies and government, the relevance of proposing alternatives in the regulatory and planning frameworks on the figure of associated management and social participation in urban management was explored. The difficulties of the intervention (material recovery, management, administration, economic sustainability) were also identified, resulting in a trajectory of action that represents a novel approach to local urban management in Montevideo. The greatest challenge at present is identified in accompanying the implementation and management phase of these advances, recognizing them as valid processes and instruments of Territorial Ordering and Urban Planning through management offices that work with the competences mentioned above and in the long term to multiply their resources by coordinating the various sectoral directorates (economic/social/artistic/environmental) of the government in the territory.

From a civil society and social movements point of view, taking into account the self-organization of social movements and diverse actors in the territory, we can say that the process was highly attentive to valuing this component, promoting the constitution of a network of collective actors for the recovery of abandoned spaces called Red Recuperada (Recovered Network). They continue working nowadays promoting the recovery of buildings for civic uses, plans to use empty land or plots to repair the damaged ecological network of the Bay of Montevideo, as well as public spaces or underused large buildings that can provide missing services to improve the quality of life and retain low-income populations. The Red de Colectivos Recuperada is also constituted as a political subject that, beyond the facilitation of the University, will have a direct role in the negotiation and construction of common goods and desirable infrastructures with the reference institutions in which working together can constitute in the long term urban ecosystems of common goods.

Summing up this introduction, this experience proposed the empowerment of intermediate agents and agencies not focused on traditional actors (governments/market). It states that in the revitalization of the city, the necessary strategy to build a new model is to act a distributed urban regeneration, as a fabric, a rhizome or urban ecosystem, which does not depend exclusively on large capital and private investment. That is, following Bruno Latour (2008), an assemblage founded on cooperation between a heterogeneous set of actors (human and non-human) that unite and find their strength in a common project, leaving the door open to a new type of urbanism with a constant institutional monitoring that facilitates, empowers and invests resources to implement economies, cultural expressions, and ecologies in the ecological and social transition towards a new city with socio-spatial justice.

Montevideo capital of Uruguay, a long story of displacement

Home to 1.3 million inhabitants, the city of Montevideo, the capital of Uruguay, sits in a natural harbor. As urban planning researchers Tom Angotti and Clara Irazábal (2017) note, colonizers planned Montevideo, like other Latin American cities, as a key 18th century point to facilitate the exit of the region’s natural wealth through its ports.

Montevideo expanded in the 19th and 20th centuries through the creation of working-class neighborhoods that would make up the intermediary city, guided by private development and a strongly benevolent state that provided necessary services. Urban historian Julia Yolanda Boronat (2017) describes Montevideo as a lively place. The establishment of various private industries–such as tanneries in the Nuevo Paris neighborhood, textiles in Maroñas, La Teja, and Capurro, an oil refinery in La Teja, slaughter house in the Cerro neighborhood, rubber and tire factories in Villa Española, the railways in Peñarol, and private tram companies throughout the city–defined a new structure that gave vitality to the city until the 1970s. Meanwhile, with the creation of the National Affordable Housing Institute in 1937, the state contributed to densifying the urban fabric. Immigrants arrived both from rural areas–due to the stagnation of the livestock sector beginning in 1930–and from foreign countries, as a consequence of European wars. The consolidated city, a term describing well-serviced and central areas of the urban grid, responded with an urban-architectural structure of services, schools, hospitals, and markets, while in housing issues, equity-seeking measures such as rent control in the 1940s and wealth redistribution policies sought to promote social cohesion.

Families populated different areas of the city according to where they could afford rental prices. In the 1960s, 60% of the capital’s families lived in rental houses, according to data from Uruguay’s Investment and Economic Development Commission (Álvaro Moreno 2018).

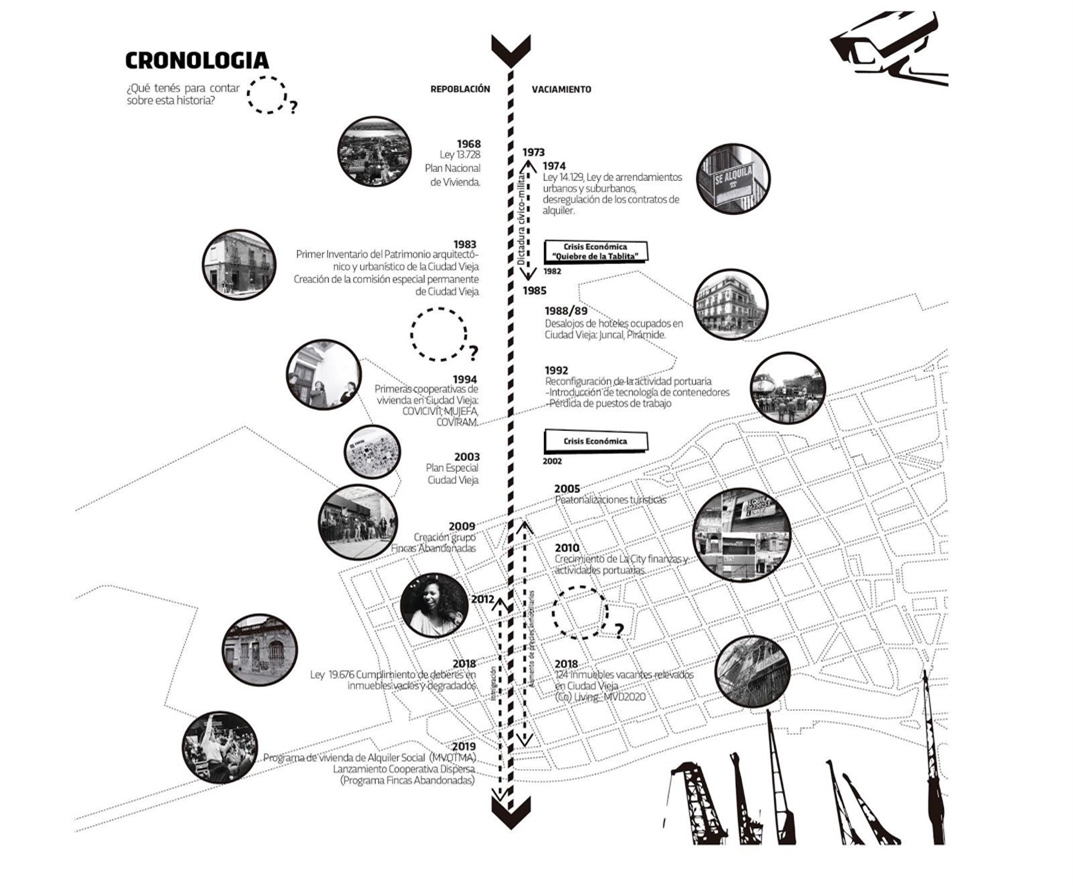

As Europe recovered and markets concentrated in the United States, many factories in the city closed, leaving entire families unemployed. This was compounded by the neoliberal onslaught in Latin America, paired with military dictatorships in the 1970s and 1980s, which in Uruguay brought measures such as rental deregulation in 1974. Despite the promise of market self-regulation, families’ situations radically changed. Inhabitants could not cope with rising rents–that is, the cost of the consolidated city.

The housing censuses in the following years documented a decrease in renters and an increase in property owners. The shift represented new modalities of ownership; families took on debt to purchase houses with 20 or 25 years of loan payments, or authorities registered informal occupations to give property titles to residents living in peripheries far from the city center. Rising prices and the inaccessibility of rental housing accelerated the emptying out of the consolidated city. As a result, traditional neighborhoods declined while informal land occupations on the urban margins increased (Martínez 2012).

On the other hand, people who did not want to leave the neighborhoods where they were born, their family networks, or their work environments, enacted several spontaneous forms of resistance in the face of their inability to pay their rents. One was to occupy real estate properties; another was to live in boarding houses and tenements–buildings with shared bathrooms and laundry spaces that rented rooms where mostly Afro-Uruguayan and immigrant families lived in overcrowded conditions.

However, the state often harshly combatted these resistance efforts. Under real estate industry pressure in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, authorities evicted families and entire buildings that had organized occupations (Romero Gorski 2003). According to the research center Neighborhood Territorialities in the Contemporary City at Uruguay’s University of the Republic, the expulsions were also coercive, one by one, and offered evicted residents only temporary accommodation for 120 days, or registration in the Registry of Emergency Housing Applicants, which the government would later shut down due to its inefficiency in offering permanent housing solutions.

The evictions always hid an ideological backdrop: private property prevailed over other rights. The motto “the city is for those who can pay for it” was becoming more explicit under the governments in power. Stories of evictions in Barrio Sur and Palermo, for example, two neighborhoods in Montevideo’s central coastal area famous for occupations and boarding houses or tenements, testified to a marriage between the liberal investments and fascist ideologies. They underlined the contrast between social privileges and the denial of rights, such as when, in the 1970s, Uruguay’s civic-military dictatorship “deported” populations, especially Afro-Uruguayans, living in central tenements to abandoned textile factories in the periphery. Elizabeth Suárez, director of Afro-descendants’ programs in the government of Montevideo, explained how these former factories, located in marginalized areas of the city, were like “concentration camps” where the military regime took the Afro-descendent population. “The situation was one of general impoverishment; crime and misery were associated with African ethnicity,” she explained.

With the return of democracy in 1985, the state launched a five-year plan to provide 5,000 new homes and compensation measures, such as home construction loans. In a general context of an impoverished populace, the policies generated uncontrolled growth of the informal and expanding city, according to research by urban planner Edgardo Martínez (2011).

Five years later, in 1990, the first left-wing government in the capital–the first left-wing government in the country’s history, resulting from a coalition of social movements and emerging parties under the banner of the Frente Amplio (Broad Front)–carried out a gradual process of rethinking proposals for Montevideo to conceptualize and organize the city through public policy. This was similar to what journalist and sociologist Marta Harnecker described in the context of the return of democracies in the region: a process with the weight of responsibility and enthusiasm for active social participation in imagining structural transformations through public policy.

Urban policy from center to periphery

Uruguay’s political stability has enabled the development of a virtuous collection of urban policies and programs, within one of the most robust welfare states in Latin America. However, about the issue of the emptying of the city, there were limited instruments, such as taxes on idle land and improper construction, implemented in 1952 and later incorporated into the constitution, as well as timid urban planning, which left voids to be filled. Specific decrees and laws that arose in recent years still lack the concrete programs and financing needed to implement them. The Frente Amplio–the only political party with some currents that question the primacy of private property and the real estate power on urban development–was concerned about resuming the planning process that the dictatorship had interrupted with its aggressive deregulation of the rents and insertion of Uruguay into the global economy’s logic of flexibilization and outsourcing. The strategic vision for Montevideo, enshrined in the 1998 land-use plan known as the Plan de Ordenamiento Territorial (POT), sought to maintain and defend the city’s multi-class and integrated character and “ensure the right to the city” (Altmann and Goñi Mazzitelli 2021).

However, as urban planners Alicia Artigas, Manuel Chabalgoity, Alejandro García, Mercedes Medina, and Juan Trinchitella (Artigas et al. 2002) pointed out in evaluating the plan in 2002, successive governments failed to make progress on implementing urban interventions aimed at creating central spaces for people who had been expelled from the city center. From 1990 until 2000, left government efforts in the city addressed pressure from displaced populations residing in the periphery, enabling the frequent phenomenon of informal land occupations and self-construction initiatives. In other words, the government did not promote the replacement or recycling of buildings in traditionally central areas. They did not negotiate with the owners of empty homes or manage investment, resulting in the deterioration of the housing stock. There was also an under-utilization of existing urban infrastructure and services, as well as a degradation of public space, especially in local streets, now only fulfilling their basic mobility function after losing their community use within traditional neighborhoods.

Rather, as the above authors point out, the market has answered the demand for new city centers with shopping malls and big-box stores in metropolitan mobility points. For many years, these public policies, which responded to emergencies, prioritized providing housing quickly. This generated what Carlos Acuña and Alvaro Portillo (1990) have called a “generalized urban regression” that expands the city not by natural population growth, but by following the whims of the market.

In 2010, this dysfunctional situation became expensive and evident for Montevideo’s government, forcing the city to make massive investments in infrastructure, services, social, educational, and public health policies to address population increases in the peripheries. Complicated family situations, as anthropologists Marcelo Rossal and Ricardo Fraiman (2009), as well as Eduardo Pedrosian (2013) have pointed out, gave way to violence as criminal networks and “narcos”–gradually gaining a presence in Uruguay–exploited marginalized environments, leading to further segregation.

Retake the Downton: abandoned plots and the Right to the City

Meanwhile, efforts to make Special Plans in the new millennial for some historic and heritage neighborhoods produced different strategies for a few consolidated areas, however, the main protagonists were academics and inhabitants. Only a small percentage of these plans came to fruition, usually accompanied by housing cooperatives–a fundamental social actor–that received vacant lots and empty houses. The most emblematic cases were the special land-use plans for Barrio Sur in 2002, for Montevideo’s historic center, the Ciudad Vieja, in 2004 (Intendencia de Montevideo 1998), and for the Goes neighborhood in 2010. These interventions have the figure of Master Plans, however there were little power to convince the private owners and the main actions were done by public investments thanks to international cooperation, as Goes Plan which was an emblematic experience by recovering the neighborhood’s centrality focused on reviving an old agricultural market, and give public land to cooperative housing.

It was only in 2008 that the government passed the National Land Management and Sustainable Development Law. That law clearly defines owners’ duties; to use, conserve, recover, and restore property, as well as the state’s duty to penalize noncompliance by expropriating properties abandoned for more than 10 years and returning these seized goods to the Public Land Portfolio (MVOTMA 2008). These regulations, together with other decrees, began to create an arsenal of legal instruments with which regional governments (intendencias) could implement housing measures.

In 2010, the rental situation led to a new burst of social organizing that reactivated the cooperative movement for the right to housing, introducing a variant of the “right to the city” with the idea that “location counts.” The movement began to think about occupying central lands and even reactivating the dormant Special Plans, such as the one in Barrio Sur. Members of these cooperatives also pushed for social housing plans for designated areas to be executed. This effort won 318 cooperative homes in the central coastal area over the course of five years.

Other processes in those years forced the regional government to think about increasing its housing stock in the Public Land Portfolio in the center. A POT progress review in 2010 once again raised the under-utilization of building stock and existing capacity in central areas as a priority issue (Intendencia de Montevideo 2015b). The Departmental Land Use and Sustainable Development Guidelines approved in 2012 defined the main challenges for the city today: the degradation of natural resources, socio-territorial segregation, habitat precarity, urban expansion (including the rising cost of living in the city and the loss of rural land), the under-utilization of existing capacity (including degradation and emptying), and the demand for land for infrastructure and productive purposes (Intendencia de Montevideo 2012).

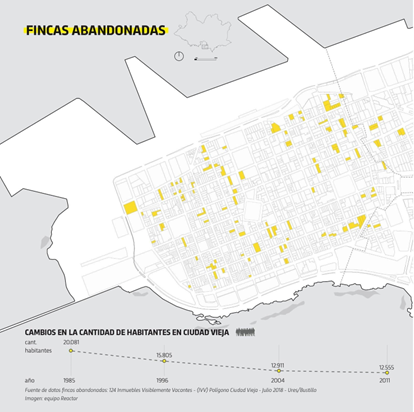

In 2014, the Defensoría de Vecinas y Vecinos ombuds office, an institution that investigates and resolves Montevideo residents’ complaints against the government, hired a team of researchers to conduct a survey of visibly abandoned buildings in some central areas. Gonzalo Bustillo and Mariana Ures (2016) concluded that 3.26% of buildings in these areas had been visibly abandoned, while empty housing stock–units abandoned, for rent, for sale, or other otherwise temporarily uninhabited–totaled 8.82%.

Criticism over the expulsion of people living in precarious situations from the center to the peripheries gained strength in 2017. Public debates on the subject appeared in the press and grassroots organizations began to take action. In the historic center, one of the neighborhoods under greatest pressure from real estate firms, the residents’ movement for the right to the city was born. The movement even questioned the Uruguayan Federation of Mutual Aid Housing Cooperatives (Fucvam), the largest and oldest movement dedicated to housing issues. As architect Álvaro Moreno (2018) has noted, the cooperative movement’s self-criticism consolidated a new focus within its mission: It became aware that in the struggle to provide housing for low-income families, the location of cooperatives within the city was important. Obtaining land in the peripheries for large cooperative complexes, which was the common practice historically, increases socio-residential segregation and strains people’s living conditions. That’s why it became a priority to reach agreements with the Montevideo government to access central areas and reverse this situation (Delgado et al. 2015).

Meanwhile, on the national stage, lawmakers approved the National Strategy for Access to Urban Land in 2018, which, based on strategic actions, will seek to support local governments in recovering consolidated areas in their cities (MVOTMA 2019). In 2017, the Montevideo government reactivated the Inter-Institutional Abandoned Plots Group, a program created in 2009 that brings together technicians and officials led by the Montevideo Department of Urban Development. The Abandoned Plots Group studied the best legal instruments to force owners to fulfill their duties and how to expropriate properties when needed. The Group’s objectives focus on the “recovery of abandoned properties in the central and intermediate area of the city to help solve problems associated with abandonment: buildings at risk, environmental degradation, social conflict, and citizen security.” The Group also has proposed transforming real estate “into assets for the city, becoming part of available urban land.”

To this end, the Group has carried out several actions through agreements with ministries, public agencies, and other stakeholders. Its initiatives have included day centers for homeless people, temporary shelters for mothers with children facing housing emergencies, and rental social housing where families can access collective housing at a rate assessed as an affordable percentage of their income. Meanwhile, in conjunction with the cooperative movement and the Faculty of Architecture and Urban Planning at the University of the Republic, the Abandoned Plots Group has begun to explore the idea of dispersed cooperatives. These are housing cooperatives based on mutual assistance, self-management, and collective ownership, but designed for the consolidated city, where several families will constitute a single group divided into different empty buildings. In addition, in partnership with civil society members, some buildings will be earmarked for civic uses, such as La Casa Trans for LGBTQI+ groups to promote their struggles.

Reactor Urban Laboratory of affective micro interventions

In 2019, by virtue of an agreement between the University of the Republic, the School of Architecture, Design and Urbanism and the Empty Houses Program of the Municipality of Montevideo, a review process of these policies was initiated with the aim of identifying the strengths and weaknesses of these programs, as well as the mode of urban regeneration that can involve a systematic and organized action from citizen initiatives in the recovery of abandoned properties.

Two major cycles and four phases (two per cycle) with their specific actions were identified with the program:

acquisition of properties for the public land portfolio for the program with the phases of mapping and identification of suitable properties, and expropriation or solution to abandonment.

management in the definition of new uses and agreements for the properties with the phases of identification of interested groups, co-design with them of uses and recovery/rehabilitation projects, and signing of associated management agreements with the Municipality of Montevideo.

As mentioned above, the major housing issue was channeled through ministerial programs for social rental and, in agreement with the Federation of Housing Cooperatives for Mutual Aid, for cooperative housing. Although the Program is only four years old, its positive results are already visible in the growth of the Social Movement for the right to the city, since the proposal of a pilot project for a dispersed cooperative, which will provide housing for 20 families in the historic center of the city, led to a call for applications from more than 350 families. These families, together with the activists, decided to form 5 cooperatives, beyond the first 20 housing units that the city government made available to continue building projects meant to facilitate the access to housing in the historic center.

Regarding other possible uses, the need to restore the properties to a useful use for society was discussed, as dictated by various laws, understanding that the expropriation of properties will be a delicate issue, in a world in which the market and private property are more important than the logic of equitable and common construction of the city. Therefore, it is necessary to communicate the actions of urban regeneration, to explain to what extent private property has the responsibility to maintain its assets in use and good condition for the benefit of the entire community, and if not, how the city government has the right to expropriate it and return it to society. It is here that restitution begins to discuss whether it should be sent to auction and return to private hands, or whether a stock of public lands can be created, considered urban commons that can encourage middle and low-income populations to find accessible services, as well as to propose economic, social, and cultural activities necessary to recreate the intimate dimension of a neighborhood. A clear example of how the market has destroyed this condition is the extinction of small stores due to the invasion of supermarket chains that displace them from the neighborhoods. Public policies and programs are needed to make available the civic uses necessary to improve the quality of life of the population and avoid the degradation of the city.

To this end, the Participative and Affective Urbanism research group of the Institute of Territorial and Urban Studies was convened to devise and coordinate the process of deliberation and co-design of civic uses for those vacant properties not destined for housing solutions. Civic uses are those uses that benefit the community but are not the traditional state services that constitute the urban standards by which cities are designed (schools, hospitals, public spaces, urban greenery, etc.). We refer to urban standards as those infrastructures and services that a welfare state should ensure, leaving to the market and to spontaneous social arrangements all other areas of the urban economy, art and culture, leisure, and in recent times, with the changes in the labor market and in the composition of families, also the new types of care that do not yet enter as constitutionally acquired rights (Baioni cited in Patti and Polyak 2017).

The simplification that the commodification of the city generates with the current growth mechanisms generally cancels the opportunity to exchange at the local level on the things that are needed for the common life of its inhabitants. That is to say, what characteristics are desired for a neighborhood, what are the activities and spaces to be built to renew the human need for socialization, the diversity of religious, cultural, and economic activities, or the equipment needed to mitigate the effects of climate change, among others. These demands differentiate urban environments and give them their own identity. However, the state’s policies and resources applied to services are not always adapted to this diversity and updated to the ecological challenges of their times. In general, governments tend to reproduce, manage, and maintain services from the moment of their creation, until new demands or extreme requirements cause them to change.

In recent decades, the “great acceleration”, as scientists call the territorial transformations of the extractive and predatory economic matrix, have resulted in the need for new paradigms that consider ecological aspects as central, as well as care and social justice.

To work on this, a methodology was proposed that, on the one hand, will make an open call to groups and projects that wanted or needed spaces in which to carry out activities with civic purpose. Using transdisciplinary techniques to value the experiences and forms of local organization, it was proposed to discuss the current transformations and the imminent need for an ecological and social transition, with the purpose that the proposals could benefit central aspects for life. These included private economic ventures, but above all, the proposals had the objective of promoting ecological restoration, the creation of job opportunities in transformative economies, as well as cultural and collective care to improve the quality of life of the urban territory where they would settle. On the other hand, we tried to understand to what extent the state can support this network of groups in the recovery and shared management of abandoned properties, which are public heritage, and therefore it was necessary to study new urban programs, as well as mixed legal figures for their management; public-private with civic purpose, public-organized civil society, public-neighbors, etc., to ensure their operation, multiplying the resources of local governments.

With these ideas, an Urban Laboratory of participatory planning was created, to put into practice a pilot process that confirms in practice these hypotheses. The team has a multidisciplinary composition: anthropologists, architects, urban planners, artists, with advisers in ecology, economy and legal studies. It was decided to start with the neighborhood with the highest concentration of vacant properties, the historic center of Montevideo, called Ciudad Vieja, installing the Laboratory in the Rehabilitation Office of the Municipality, which has historically taken care of the historic architectural heritage of the area.

First of all, a historical and bibliographical background review is carried out to reconstruct the reasons for the abandonment and deterioration of the building heritage, in addition to the general condition of the rehabilitation experiences of urban economy districts, and the precedents in mixed legal forms of management.

On the other hand, a mapping of actors interested in building projects for the recovery and use of real estate with collaborative urbanism methodologies is carried out. Finally, a process is developed with workshops and tours of recognition of good practices, which produces an agenda of civic uses, with more than 40 proposals that are subdivided into four areas:

urban ecology,

transformative economies,

heritage and tourism,

art, culture and care.

The process consisted of 4 phases:

Historical-artistic-ethnographic explorations and actors mapping; through social research, territorial stakeholders interested in working on the recovery of properties were detected, as well as existing citizen initiatives for the recovery and management of land or properties that were previously vacant.

Affective Heritage Map. With the above, we built what we call the map of affective heritage, with the support of the Spanish group Vivero de Iniciativas Ciudadanas (Citizens Initiatives Incubator), and architect Mauro Gil Fournier in the valuation of local practices and the creation of a repertoire of international best practices that consolidated in the collective thinking the possibility of creating a recovery from the local level.

Playful-collaborative workshops for the elaboration of the Agenda of Civic Uses. Those interested in forming working groups for the recovery of buildings or vacant land in the area were publicly invited to workshops aimed at structuring individual demands and putting them into a system with others to strengthen the potential groups to recover properties. From the materials collected, four thematic axes were identified: Transforming Economies; Art, Culture and Care; Urban Ecology; and Collaborative Ways of Living, to which the Heritage and Tourism axis was added in a second instance. The proposals were organized around them, forming an Agenda with more than 50 proposals for Civic Uses in vacant buildings for the historic center.

Co-design of the first prototype for the recovery of abandoned buildings Casa de Piedra (Stone house). Through workshops of architecture, economic sustainability and legal management, the first recovery prototype was created and started to operate, opening its doors in December 2020 to the collectives and enterprises that formed the motor group of the project.

Where everything starts, the historic center of Montevideo

The historic center of Montevideo was chosen to be the first neighborhood in which applied this methodology, as long as has been one of the areas with the highest levels of population and buildings abandonment in the city. According to population censuses, it registered a steady decline from 1985 with 20,081 inhabitants to 12,555 in the last census of 2011. During this period, other commercial, economic, sporting, artistic, and social activities related to the residential use of the neighborhood also declined. The factors that led to this situation are manifold and have different relationships with each other and with the economic, political, and social transformations in the urban, national, and international spheres. Studies mention the 1940s as a transition date with a residential movement out of the neighborhood of the wealthier inhabitants, towards the east coast of Montevideo (Romero Gorski 2003).

In the decade that followed, Uruguay began a long period of economic decline, with the deregulation of the rental market and the forced eviction of conventillos and tenement houses dwellers in central areas of the city (Y. Boronat, Goñi, and Mazzini 2007). On the other hand, the growing development of the financial activity in Ciudad Vieja, which became a banking and customs office area of the port, put the residential character at a disadvantage, with the demolition of the historical heritage and the reconstruction of parking lots and new infrastructures functional to the new prevalent activity. Only a few intellectuals, architects, and historians opposed the logic of the market that acted in the demolition of heritage to build ex-novo structures, creating the Urban Studies Group, which introduced the concept of Heritage Inventory and demanded the protection of buildings with historic architecture. In the 1990s, the emptying of the downtown area of Montevideo continued, both in the residential and commercial dimensions.

At present, different vectors of re-population can be identified, in which different trends of international migration and movements within the city are linked. The urban centrality and historical heritage character of the Ciudad Vieja attract the attention of middle class people and foreigners, Argentinians, Europeans, and North Americans, producing a process of gentrification. The policies aimed at protecting and enhancing the historical and heritage character of the Old City converged in a series of public and private actions that positioned the city of Montevideo in a circuit of the globalized tourist market (Martinet 2015). This set of elements led to a rise in the value of urban land and attracted national and international investors, who appropriated the rent differential generated through the businesses they do with properties through real estate developments, which benefit from incentives from public agencies (García et al. 2019), or as (Sassen 2003) and Ana María Vásquez Duplat (2017) explain, by acquiring properties that function as a capital reserve, thanks to their location and central urban land value, even if they are degraded and are not rented or sold. On the other hand, Latin American migratory flows stand out, with an important wave of immigrants from Peru in the 1990s, with a significant influx of people from the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Colombia, and Cuba since 2012 (Ministerio de Desarrollo Social 2017), who strategically choose the central areas for their provision of services and job opportunities. These populations generally live in boarding houses, large heritage houses that rent rooms for each family per day or per month, with no guarantee, in precarious physical and hygienic conditions (Uriarte, Fossatti, and Novaro 2018).

The architects Mariana Ures and Gonzalo Bustillo identified 124 “visibly abandoned” properties in the area, of which the Abandoned Houses Program of the Municipality of Montevideo corroborated that 24 properties, including houses and vacant land, could be expropriated due to the conditions and the debt with the municipal government. However, they encountered great difficulties when it came to expropriation, since according to the Municipality’s lawyers, the judicial processes of expropriation, particularly those in which the debt with the Municipality is greater than the value of the property and therefore there is no economic compensation but only expropriation, are also highly resisted in the judicial sphere that defends private property rights, even in the face of national laws that demonstrate the damage to the community, and slows down the practices (Gonzalo Bustillo and Ures Álvarez 2016).

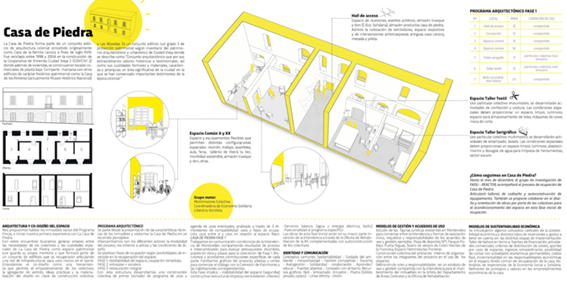

Casa de Piedra: co-design and assisted recovery for a new urban common

As we stated before, more than 40 proposals emerged from the process of explorations and workshops at the Historic Centre, grouped into thematic categories, in particular, to demonstrate the need for the Abandoned Houses Program of having a real intersectoral coordination in the implementation, monitoring and management phase.

While the participatory workshops surveyed the interest of collectives and built a network for the recovery of properties, the Municipality worked on the expropriation of the 24 properties identified in the historic center. Twelve were quickly obtained, including vacant lots, half of which were destined for social housing, through the system of housing cooperatives by prior savings or mutual aid. Of the remaining six, only one was in a condition to be quickly intervened for Civic Uses, since the rest were ruinous lands or buildings in danger of collapse. However, this was enough to develop a prototype that consisted of testing a co-design methodology, a building recovery program and associated management agreements for their maintenance. The building named Casa de Piedra was inaugurated by its collectives in December 2020, after a 6-month process of co-design and building recycling assisted by the Municipality, the entrepreneurs and collectives involved, who finalized the proposal including five of the uses contained in the Agenda; textile workshops for youth and LGBT movements, a warehouse for products of the transformative and circular economies, a women’s bicycle mechanic workshop for bicycle repair and assembly of other vehicles that promote sustainable mobility, leaving spaces for printing and publishing collectives, as well as for an audiovisual and social marketing production company, with rotating uses.

Prior to the start of the participatory workshops, criteria were introduced for the development of the prototype and for the formation of the space management group, based on the concepts of urban ecology, care and transformative economies. The generation of shared-use projects was promoted among several organizations, conceived as a common good for the neighborhood and the city and as part of a future network of infrastructure recovered for civic uses.

The methodological process that was carried out responds to the theoretical approach of strategic planning and participatory design created by architect Cristopher Alexander (1977) and adapted by the local group according to the needs and scale of the intervention. The co-design work on the architectural heritage aspects determined a negotiation on the possible uses among the groups interested in the property. The groups in charge of managing the space and assuming the rights and responsibilities involved were constituted as a motor group. The resolution on who would actually form the motor group of the space was worked throughout the co-design workshops, in a decision process by the method of creative consensus (Susskind and Sclavi 2011). Based on the needs of each collective and the possibilities of the physical space, it was collectively understood that the space was adequate and compatible for three collectives: Coordinadora Nacional de Economía Solidaria (National Coordinator of Solidarity-based Economy), Liberá tu bicicleta (Free your bike) and Multimostrx Colectivx (LGBT design- textile enterprise). The workshops were developed in a predetermined period of time of two months, were weekly, consecutive, approximately 2 hours long, each one focused on a theme and of cumulative development. The central themes addressed were the construction of an urban common in based on for criteria:

values and operating criteria,

architecture and physical aspects,

economic sustainability of the project,

legal forms of the management agreement.

Casa de Piedra shows a successful pilot experience of collaborative public policy in which the actors involved are present from the identification of needs and resources to the implementation of heritage recovery, self-recycling and subsequent management. It is part of a colonial architecture building complex originally conceived as the Lecocq family house at the end of the 18th century. It was recycled between 1998 and 2004 with the construction of the Ciudad Vieja 2 Housing Cooperative (COVICIVI 2), where, in addition to housing, ground floor commercial premises owned by the Montevideo Municipality were built, some of which have been unused since that time. It is a property with heritage protection, declared a National Historic Monument.

The first theme developed was architecture and physical aspects. With these meetings we tried to generate links between the needs of the collectives and the spatial qualities of the Casa de Piedra as a heritage space that keeps its own memory and that will be part of a set of buildings that will be recovered articulating a network of infrastructures for civic uses in the neighborhood. We understand the co-design as a method that allows the empowerment of collectives, the aggregation of meaning, ideas, practices, and the materialization of design in the key of collective construction.

A temporary structure was proposed for the incremental recovery of the building in 3 phases considering the physical conditions of the space and the amounts of investment available for the intervention works. During the Reactor 2020 workshops, the project for phase 1 was developed and a draft of phase 2 was proposed.

STAGE 1: Habitability of the first floor space and basic services. STAGE 2: Reconstruction of the mezzanine, enabling 60 m2 of use area. STAGE 3: Integral restoration.

STAGE 1 works are made up of initial public investment interventions by the Montevideo Municipality and other masonry works, recycling of openings and construction of equipment by the collectives of the motor group, carried out through self-restoration with technical advice Montevideo Municipality officials, University of the Republic team, and specialist builders.

Secondly, economic sustainability was addressed. Together with the economist Rodrigo García (UDELAR), the concept of economic sustainability was studied, understood in a classical way linked to a business logic and referring to the capacity to organize and manage resources with the perspective of generating profitability in a responsible manner and in the long term to improve and maintain the property and its uses.

Clearly, it is the collective’s vocation to prioritize the use value (needs of the community) over the exchange value or profitability of the activities to be developed in the property. The general objective of the work on economic sustainability was to contribute to the collective elaboration of criteria for the administration and management of the resources linked to the activities to be developed in the properties of the Abandoned Houses Program, taking as a case study the Casa de Piedra, considering its material specificity and location and the role of the participating actors in all the phases of its transfer, recovery and management.

Participatory management model

Finally, the legal forms of the management agreement were discussed. The implementation in the Casa de Piedra prototype of a participatory management model, which includes the recovered properties as urban commons, required learning about existing experiences and studying the regulatory frameworks in force, both in Uruguay and in other countries. A description and systematization of background information on the associative legal schemes available under Uruguayan law to serve as a basis for associative groups and some recent experiences of use agreements by the departmental government that could be used as a reference were described and systematized. The figure commonly used for the signing of contracts between the Municipality of Montevideo and social organizations is the assignment of the use of a property to a civil association (CA). In order for a CA to operate, it requires the approval of its bylaws by the Ministry of Education and Culture (MEC), which must contain provisions on its internal governance provided by law. However, these generally do not adjust to the dynamics of the social collectives, which usually have organizational and operational mechanisms different from those pre-established in the law. When transferring certain powers over departmental fiscal property, such as the use for a specific period of time, the Municipality is subject to two conditions: on the one hand, the contracting party must have legal status and, on the other hand, it must obtain the authorization of the Departmental Board if the powers transferred go beyond the period of government. At the same time, the transfer modality largely relieves the Municipality of the possibility of taking part in the care and recovery of the building (which, being of a heritage nature and requiring refurbishment work, requires expenditures that exceed the possibilities of the collectives), as well as of influencing the activities and uses of the space through participation in its management.

All these elements formed the basis for the collective elaboration of a proposal for the management of the Casa de Piedra by the member collectives of the motor group. Finally, an agreement was reached on the associated management modality between the Cityhall-Collectives-Municipality for a five-year period, renewable for the same period–IM, 2020. The coordination team was formed by a representative of the Land and Housing Service of Urban Development, a representative of Municipality B and a representative of the motor group. The role of this area is to ensure compliance with the objectives of the agreement, establish annual lines of work, manage economic and material resources, propose internal operating regulations and coordinate with the Municipality’s units.

Conclusions : reclaiming the right to the city by building urban commons in abandoned plots

In the urban history of Montevideo, as in other cities of Latin America, the dispute over the consolidated city has been a cyclical reality since the rise of market deregulation and liberalization. Meanwhile, the possibility of accessing central, coastal, urban land became increasingly exclusionary. Over the last 30 years, left-wing policies focused on improving the living conditions in peripheral neighborhoods. This responded to the inherited mission of the welfare state and a cultural conception of private property as a definitive solution and a basis from which to work for other rights. This approach settled families in the city’s periphery, emptying historic and central neighborhoods and impeding mobility in a way that reinforces socio-territorial segregation.

In addition, as Ana María Vásquez Duplat (2017) and Ermínia Maricato (2017) demonstrate in the cases of Argentina and Brazil, respectively, the phenomenon of urban extractivism is also growing in Uruguay. This process, which also has international dimensions due to large foreign investment, continues to displace residents of the consolidated city. Only recently, thanks to citizen and neighborhood movements fighting for the right to the city coupled with a rethinking of the cooperative movement’s urban role in settling families in peripheral neighborhoods, has there been a shift to understanding the need to change course.

However, confronting the challenge of urban revitalization in abandoned consolidated areas once their original populations are uprooted is extremely complex. Efforts must be long-term and integrate consideration of both social aspects as well as economic and cultural opportunities in planning processes. If it is desired that low-income families base their survival on the social solidarity networks characteristic of popular neighborhoods and subsequently return to the consolidated fabric, it should be borne in mind that these conditions must be recreated. In addition, initiatives must have the necessary social and state support for local economies and family needs such as child and elder care, which typically demand a precarious labor market with actors subordinated to a logic at odds with traditional family and neighborhood life.

Although the experimental Urban Laboratory Reactor, as well as the Empty Houses Program are only five years old, it has had positive results that are already visible in the growth of different experiences that empower the movement for the right to the city. However, private property owners and real estate resistance did not wait. Lawyers for the Montevideo government involved in the expropriation of abandoned houses or negotiations with owners–sometimes real people, in many cases transnational capital–have said there are many difficulties taking action against private property.

In cases where real estate debt with the state exceeds market value, expropriation takes an average of 24 months. In all other situations of abandonment and degradation, understanding how to act is extremely challenging. The fundamental discussion always returns to the possibility of having collective or common use models that disarm the logic of private property and profit. Through virtuous feedback processes–with all their internal conflicts and challenges of distrust–but above all through the legitimacy that government recognition gives to self-organization and resistance movements in core neighborhoods, a concrete vision for the development of the city is emerging and growing. These are radical policies that can challenge market forces by removing abandoned buildings from real estate speculation.

The question is also how public policies of cooperation between different actors, and hybrid uses can collaborate by enabling innovative ways to support these activities. On the one hand, to escape from administrative assets that divide supports in the sectoriality of public services (schools, gardens, healthcare centers, public spaces, among others). On the other hand to recognize the passage of inhabitants from users to active builders of programing, which has seen the birth of the concept of “active citizenship” that can nimbly incorporate and update demand according to the particular uses of various groups (Muccitelli and Vazzoler 2018).

The answer could be found in the participatory process of project construction, which became central to this new form of urbanism. A government that agrees to carry out a participatory planning process must make available a real decision and agree with the participants to comply with the decisions that emerge from the process. It facilitates participatory processes by:

making available the necessary public expertise from the various divisions,

providing funding to work with the communities and the various stakeholders,

providing the necessary public resources to carry out the process,

providing the necessary public resources to work with the communities, and the various actors involved,

simplifying some administrative procedures with the aim of promoting greater understanding and involvement of the population (Patti and Polyak 2017).

Lawrence Susskind and Marianella Sclavi point out four advantages of decisions made in inclusive planning processes with facilitation methodologies:

(…) they are more efficient because they allow reaching a definitive solution in certain times and with contained costs (which are above all those of facilitation, communication and action research); they are more equitable, because they allow all interests to be equally represented if the process is guided in an impartial way and is always open; they are wiser because they allow the invention of innovative solutions where all points of view are considered; they are more stable, because those who have participated to the process will defend their results from possible external pressures, power lobbies, or personal interests (Susskind and Sclavi 2011, 128).

This analysis of implementation can be integrated with another that looks at an intermediate level between local and major orientations. This is where we find the policy instruments, i.e., those basic and strategic means or conditions without which the state renounces the possibility of solving the problems affecting society. These involve both regulations (roles, competencies are defined) and management (an organizational scheme) and resources (human, financial, technological). (Isuani 2012).

It is necessary to count on professional facilitation and mediation in these processes as the “negotiations” between the points of view and meanings that each person, group and institution bring to the collective construction processes are much more than a simple list of tasks of who is in charge of what things. As Ana Clara Torres Ribeiro, professor at the Instituto de Pesquisa e Planejamento Urbano e Regional (Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro) points out, these collaborative planning processes are a new way of building public policies, without imposing visions, nor giving a priori solutions from the technical point of view, but through dialogues within the groups that lead to a deep “understanding”, and build relevant projects, plans and programs, as well as solid bases of cooperation for what will be the real challenge of public policies: their implementation and management (Torres Ribeiro 2012).

In Montevideo, citizen innovation initiatives, local movements for the right to the city, and the rest of the participants who approached the urban laboratory process, showed their intention to innovate and also to know the power of their transformative action. The level of government that has interpreted and built an innovative agenda has been the municipal level, which nevertheless has a reduced budget and a low level of incidence on departmental policies.

The university now has the challenge of supporting it in the construction of a territorial model that functions as an urban ecosystem to link projects for the recovery of empty and degraded spaces with resources at the national, departmental and municipal levels. The key will be to provide a battery of thematic programs that articulate the resources in the territory to enable citizen initiatives, media and small entrepreneurs to take the lead and carry out a collaborative, micro and incremental urbanism that will lead the city center to an ecological transition and economic reactivation with socio-spatial justice.