The European Values Study

The European Values Study is a large-scale, cross-national, and longitudinal survey research program on basic human values, initiated by the European Value Systems Study Group in the late 1970s, at that time an informal grouping of academics. Now, it is carried on in the setting of a foundation, the European Values Study (EVS). The researchers aimed at exploring the moral and social values underlying European social and political institutions and governing conduct. At the time of the first survey, the following questions raised:

- Do Europeans share common values?

- Are values changing in Europe and, if so, in what directions?

- Do Christian values continue to permeate European life and culture?

- Is a coherent alternative meaning system replacing that of Christianity?

- What are the implications for European unity?

In order to answer these questions, a survey was planned and in 1981 interviews were conducted in ten European countries. The research project aroused interest in other countries and as a result a unique data set became available, covering 26 nations. To explore the dynamics of values changes, a second wave of surveys was launched in 1990 in all European countries, as well as the US and Canada. About ten years later (1999/2000), the third wave was launched and fieldwork was conducted in almost all European countries, allowing for investigating the causes and consequences of the dynamics of value change.

Atlas of European Values

More than 800 million people can call themselves Europeans: from Finland to Malta and from Iceland to Azerbaijan. Their cultures and societies have all been influenced by the Roman Empire, Christianity, Enlightenment and two World Wars. This communal history has not led to one European culture. The importance of God, the value of leisure time, the significance of having children and the disapproval of homosexuality all differ enormously between countries. This diversity is made visible in the full colour Atlas of European Values, made by three researchers at the University of Tilburg.

The Atlas contains seven thematic chapters. Here are some conclusions per chapter:

Europe: Europeans do not feel very European: rather they consider themselves as world citizens. People of Luxemburg have the closest relationship with Europe. In Russia, less than 2% have that feeling.

Family: 90% of the Latvians think that children are necessary for a meaningful life, whereas only 8% of the Dutch think so. Approximately 70% of the European parents expect unconditional loyalty from their children. And an equal percentage thinks that parents should do the utmost for their children, even if it is at the cost of their own well-being.

Work: The Netherlands and Iceland have the lowest work morale. For Europeans, the most important aspect of a job is a good salary. The Danish do not consider their work as very important, but are mostly satisfied with their jobs. Farmers from Eastern Europe and Turks are the only ones that are really unsatisfied with their work.

Religion: More than 60% of the Dutch call themselves religious. The importance of God however gets a score of only 4.9 in the Netherlands, compared to 9.2 on Malta. Three quarters of the Croatians believe in angels, one third of the Turks believe in re-incarnation. In Russia and Sweden, less than 10% attend a religious service on a monthly basis.

Politics: Spain is the most left-oriented country in Europe and the Czech Republic the most right-oriented one. Levelling of Income is least popular in Germany. Youth in Southern Europe value individual freedom and personal development the most. In Lux emburg, 45% would not mind a strong leader without parliament and elections.

Society: A one-night stand is acceptable only to youth in Northern Europe. There is a very wide range of acceptance to non-acceptance of homosexuality in Europe. Only 10% of the Portuguese think that people can be trusted. Poverty is ascribed to bad luck only in the Netherlands. Drug addicts are the least favourable neighbours all over Europe.

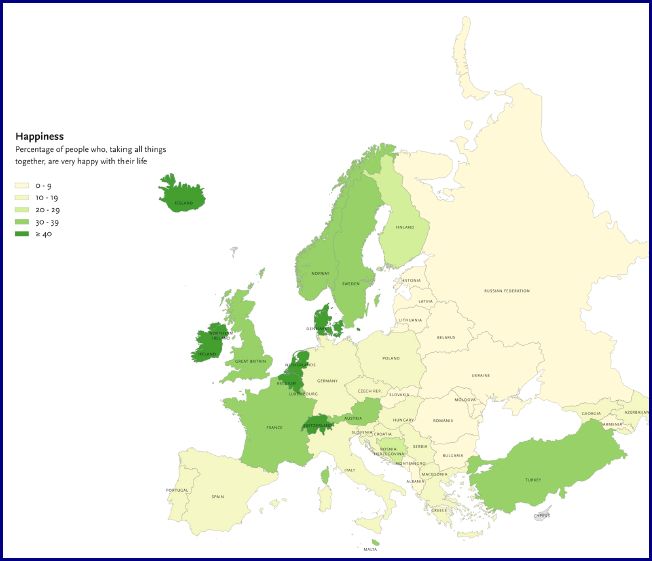

Happiness: A partner and money bring happiness, children do not. The Irish are the happiest people in Europe (47.7%). Protestants are more satisfied with life than Catholics, orthodox Christians or Muslims.

Modernity: The Danes, the Swedes and the Dutch score highest on a modernity score that includes personal freedom, tolerance and emancipation. These scores are also very high compared to countries outside Europe.

Learning to Understand Each Other

The Atlas of European Values contains all sorts of information that you, as a teacher, can use to help your pupils better relate to Europe, especially if you combine it with current events. The challenge for teachers is to make Europe more tangible for young people - a Europe characterized by unity in diversity. The Atlas of European Values provides material for numerous themes in the subject areas of geography and social studies, as well as economics and history. The atlas also contains excellent study material for the values and standards debate that the Balkenende cabinet has placed on the Dutch political agenda.

The number of Dutch citizens that are positive about the EU has declined by 6 percent since the referendum and is currently only 65 percent. A majority oppose the further expansion of the EU and especially the accession of Turkey (www.nederlandineuropa.nl). Politicians such as (former) Secretary of State Nicolaï, currently minister of government reform and kingdom relations, respond extremely cautiously: they say that they understand the fears of the population and offer reassurance by adding that Turkey can only join a decade from now. At the same time we see that countries in Europe are rapidly growing closer together - and not only in a political sense. Albanians and Ukrainians have already been working in Greece and Italy for many years (with or without a permit). During the Eurovision Song Contest last year, the overtly gay Dutch television presenter Paul de Leeuw gave his mobile number to the Greek presenter, whom all the Greek viewers knew to be diaforetikos (‘different’).

Educating young people about Europe can contribute to helping them better understand each other, after all, unknown is unloved. Returning to Turkey as an example: if people knew how western-oriented modern-day Turkey is, they would likely have less objections to the further expansion of the EU. The Atlas of European Values provides concrete information for examining such questions from another angle.

Educational Use

Currently, Tilburg University and Fontys Teacher Training College in Tilburg are working hard to make the information from the Atlas of European Values accessible for use in education. On the website www.atlasofeuropeanvalues.eu you will find the current data and maps of the Atlas of European Values. The lesson material that is going to be developed within a pilot project will be in English, Dutch and German - and in September 2007 probably in Slovakian language - but the data, of course, are suitable to be used for material in any native language. The database will gradually develop, containing a wide variety of assignments that can be used in the classroom. Pupils in various European countries will be able to select and analyze maps from the atlas and then use the database to produce new maps themselves - which will once again offer a wonderful opportunity to practice map skills during the lesson. Those who are interested can also work on collaborative assignments with other European schools.

All sorts of assignments are imaginable: for (part of) a lesson or in the form of practical exercises and as themes for subject cluster projects. Assignments can be coupled to textbooks, so teachers can use them as supplemental material or as assignments for further exploration, or they can be used separately from a method. By way of trial, various assignments have already been developed and tested at schools in the Netherlands and in Germany. The pupils and teachers responded with enthusiasm. They found that the assignments related well to their own perceptions were stimulating and that they truly provided new insights. During October last year, in the framework of the Euroweek at the Theresialyceum in Tilburg, more than 300 pupils representing 25 European nationalities worked on assignments based on the Atlas of European Values and appreciated it very much.

‘Playing It Straight’

Various assignments for a single lesson hour have already been developed with familiar and accessible themes and attention-getting titles such as ‘Desperate housewives’, ‘Playing it straight’ and ‘Helmet of Orange’ (relating to soccer). The maps in the atlas present the themes in a less threatening or admonitory manner (‘You must not discriminate!’). In each case, the pupils examine how they view a particular phenomenon, how the other class members see it, and what the views are in their own country and other European countries. In this way, they are not simply exposed to a stream of facts, but are also personally involved with the sometimes sensitive subjects. In other assignments, the pupils are asked to investigate where Philips can best establish locations in Europe on the basis of the work culture or to analyze the degree to which the communist regime is reflected in the beliefs of people in the former East Block countries.

There are also larger assignments with a somewhat broader research question. Pupils then seek appropriate maps in the atlas and the data upon which they are based. They can process the data and create a new map that answers the research question. They must support their selection, elucidate the new map information and provide verification based on other, ‘hard’, data. They can, for instance, investigate whether Turkey ‘should be’ part of the EU, which countries should form a new Core EU (such as EU Chairman Prodi proposes) and where the emancipation of women has progressed furthest in Europe (map). The website offers numerous possibilities.

While working together on teaching materials for the Atlas of European Values, the university of Bremen and Fontys University of Applied Sciences decided to bring together young students who want to become geography teachers. The exchange programme consisted of a one week programme, during which Dutch students stayed at Bremen and developed teaching materials for the Atlas of European Values they tried out in German schools and of a ten days programme of German students visiting the Netherlands to do the same. This project will be continued and probably extended.