If I’m selling to you, I speak your language. If I’m buying, dann müssen Sie Deutsch sprechen

Willy Brandt

Summary

Based on the language of economic analysis I have in this study conducted a comparative analysis of Swedish, Danish, German and French small-and medium-sized enterprises. The study is based on statistical data from several national and international sources and shows that Swedish small-and medium-sized enterprises are using far fewer languages than those in other European countries. Swedish SME companies use mainly the English language and to some extent, German and French and therefore tend to export to neighboring markets, particularly Scandinavia. On the other hand small-and medium-sized companies in Denmark, England, Ireland, Germany, Poland, France and Portugal use up to between 8 and 12 market languages, which gives them better access to emerging markets.

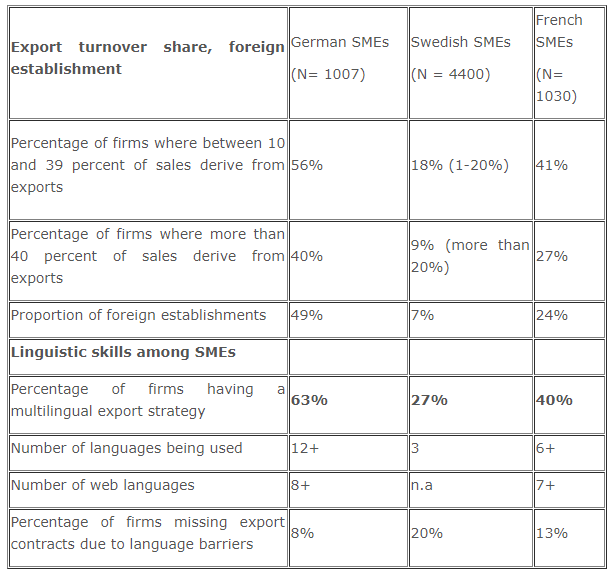

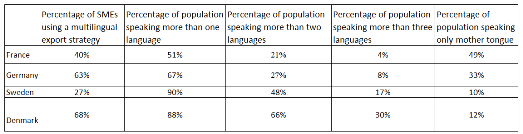

In addition, the percentage of companies having a multilingual export strategy are at 27% in Sweden compared to 68% among Danish SMEs, 63% in Germany and 40% in France. This means that the percentage of firms missing export contracts due to language barriers are much higher in Sweden and are 20%, compared to 4% for Denmark, 8% for Germany and 13% for France.

The study shows that multilingualism is more complicated than the current belief that English is the only market language. Small-and medium-sized enterprises are using to an ever increasing extent the specific language of the export market to establish themselves in new emerging markets. The market languages that are analyzed in my study in the context of SME’s export success are English, Russian, German, French, Spanish, Italian, Polish and Chinese.

Sweden, Germany and France have a similar industrial structure and compete for the same markets. I have therefore chosen to essentially compare these three countries regarding the relationship between multilingualism and export success.

The study shows that Swedish SMEs only use three market languages, mainly English. German SMEs make use of most market languages, up to 12, while the French SMEs use about 8 market languages. Here we can speak of a Swedish competence paradox. Although Sweden has a higher proportion of multi-lingual inhabitants than Germany and France, Swedish SMEs use a smaller number of market languages, which limits the export geography to Europe, mainly Scandinavia. Fewer market languages thus makes Swedish exports more vulnerable and inhibits the export performance. In this study I have shown that the use of the specific language of the export market in small-and medium-sized enterprises, among other things, provides:

- A larger number of export countries and a higher export turnover share – Greater investment in multilingual staff brings about 10.7 export countries for the German SMEs, and 7.8 export countries for the French SMEs on average. Lower investment in multilingual staff only gives the Swedish SMEs 3.9 export countries on average. Among the German small-and medium-sized enterprises 56% have an export turnover share that is between 10 and 39% versus 41% in France. The proportion of companies where the share of export turnover is more than 40% is 40% for German SMEs and 27% for French SMEs. Among the exporting small Swedish companies the export share of total turnover is relatively low. Only 2% have an export turnover share above 80%. 18% of the companies present an export turnover share between 1 and 20% and 9% above 20%.

- A larger proportion of exporting companies and a better export geography – The higher the multilingual skills among SME companies, the greater proportion of firms exporting to emerging markets and the better the export geography. Among German SMEs 43% are exporting to Central Asia, compared with 10% of French SMEs, and 8% of Swedish SMEs. This seems to be correlated with business language skills in Chinese. Among German SMEs 30% are exporting to South America, compared with 13% of French and 8% of Swedish SMEs. This seems to be related to business language skills in Spanish and Portuguese. 41% of German SMEs export to East Asia and Oceania, compared with 28% of French and 14% for Swedish SMEs.

- A larger market share in the BRIC countries – Higher multilingual skills also seem to give a larger market share in the BRIC countries: Brazil, Russia, India and China. Germany’s market share is 5.6 in China, 5.9 in India, 10.4 in Brazil and 16.8 in Russia. The corresponding figures for France are 2.1 for China, 3.1 for India, 4.8 for Brazil and 3.5 for Russia. This compared with Sweden’s figures that are at 0.7 for India, 1.2 for Brazil and 1.8 for Russia. Sweden’s market share in China has not developed enough so that it can be included in international trade statistics.

- A larger number of foreign customers and a larger proportion of foreign establishments – Among German SME companies, which have higher language skills than French SMEs, the percentage of companies billing more than 50 customers abroad are at 63%. The corresponding figure for France is 15%. Multilingual skills are also important for foreign establishment. Among German companies 49% have some form of foreign establishment, compared with 24% in France and 7% in Sweden.

Exports are affected by many variables other than language. The relationship between export success and use of market languages remains even when taking into account other influential factors such as foreign exchange differences, macro-economic conditions, corporate structure and company size, geographical location and size of the domestic market, outsourcing strategies and R & D intensity of small-and medium-sized enterprises.

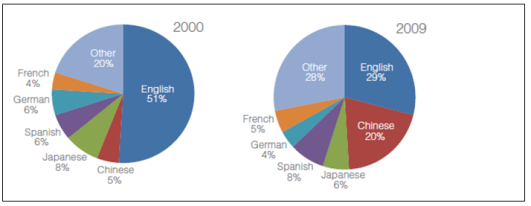

1. English is no longer dominant in world trade and internet traffic

The English language’s role as the sole language for Internet and world trade has declined and other languages are being used to an increasing extent. The Chinese language’s importance for trade relations, for example, has grown from 5% in 2000 to 20% in 2009. Meanwhile, the English language’s importance has declined from 51% in 2000 to 29% in 2009.

Global Reach Internet and the World State, 2009.

As we can see English is not the only language used in international business relations. This is due to the tendency for companies to try to use the local language of the market if possible, and if not, then one of the major European languages, such as German, Spanish or French.

When 2000 small and medium-sized companies in 29 countries were asked by the European Commission, in their study on effects on the European economy of shortages of language skills in SMEs, to identify the languages they used in their major export markets it was apparent that there is widespread use of intermediary languages for third markets. For example, English is used to trade in over 20 different markets, including the four Anglophone countries, UK, USA, Canada and Ireland. German is used for exporting to 15 markets (including Germany and Austria), Russian is used to trade in the Baltic States, Poland and Bulgaria and French is used in 8 markets (including France, Belgium and Luxembourg).

The percentage of separate instances of languages used for specifically identified export markets by companies in the sample is:

- English 51%

- German 13%

- French 9%

- Russian 8%

- Spanish 4%

- Others 15%

It is surprising that English is not more widely spread. This is due to the tendency for small and medium-sized companies to try to use the local language of the market if possible, and if not, then one of the major European languages. In Belgium, there are cases of companies using many languages, e.g. English, German, French and Dutch, as a minimum. Much depends on the multilingual receptivity of the country concerned, as well as geographical and cultural proximity: Russian is used in Bulgaria; Spanish is used to export to Portugal; French is used in Spain and Italy (European Commission, 2006).

2. Language use in SMEs

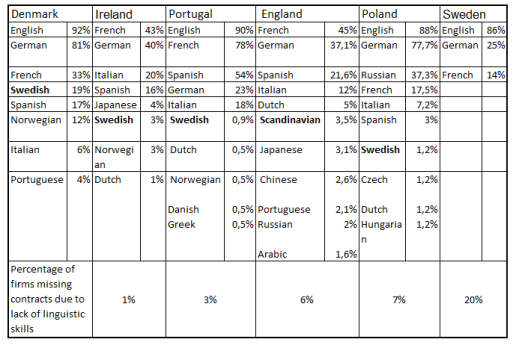

Small-and medium-sized enterprises in Europe are using to an ever increasing extent the specific language of the export market to establish themselves in new emerging markets. The languages used in the context of export of SMEs vary from one country to another. Data from six European countries show that companies using fewer market languages have a higher percentage of missed export contracts.

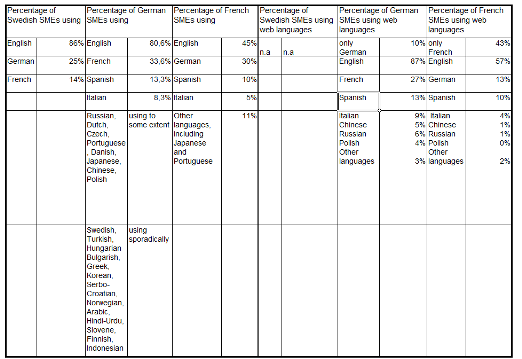

The table below shows that Swedish SMEs in the study sample make use of only three market languages: English, German and French. In the other surveyed countries, SMEs make use of at least eight market languages. In addition, the SMEs in the other countries use market languages to a greater extent than the Swedish. In Denmark, for example, 81% of SME companies use German and 33% use French. In England 45% of SME firms make use of French and 37.1% of German, compared with 25% and 14% among Swedish SMEs.

The German and French languages are thus used by far fewer Swedish SMEs than in other countries. An important observation here is that all European countries in the study group use Swedish or Scandinavian as a market language. Particularly striking is the fact that Swedish SMEs still use English as their primary language despite the fact that SMEs in England, Ireland and Scotland in their business use at least eight languages, including Swedish.

European commission, 2006; Reflect, 2002; Elise, 2001.

When we study language use among SME companies in separate countries related to export success the relationship between the two variables becomes even more clear. The table above shows that in countries where companies are using many languages the percentage of firms missing export contracts due to language barriers are lower. The percentage of SME companies missing export contracts due to language barriers are 20% in Sweden compared with 1% for Ireland, 6% for Britain, 3% for Portugal and 7% for Poland.

3. The economics of multilingualism

The link between language skills and export success has previously been studied at both a macro-economic and micro-economic level.

3.1 The macro-economic dimension

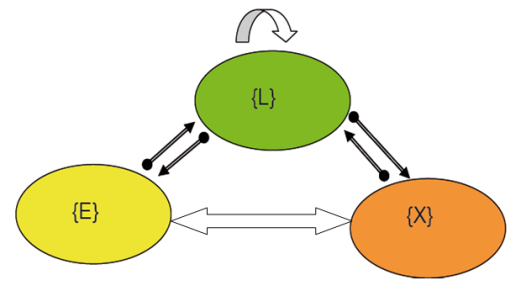

An emerging research field called Economics of multilingualism increasingly emphasizes the importance of language and multilingualism in the economy in general and export performance in particular. Multilingualism has become more and more important to economic growth. In several publications Grin (1990, 1996, 2002, 2006, 2009) has provided an overview of the study of the economics of language. Grin (2006, 2009) defines the concepts and tools of economics of multilingualism at a macro-economic level.

F. Grin 2006, 2009

Economic considerations in multilingualism constitute a relatively new development. Language is not often thought of as a discipline relevant to economics. The economics of multilingualism points to the main issue: How do language variables affect economic variables?

According to the research group studying economics of multilingualism at the University of Geneva the language diversity in Switzerland generates 9% of GDP . The researchers began by stating that Switzerland has four main languages in decreasing order of number of speakers: German, French, Italian and Romansh, which is spoken by 0.5% of the Swiss population. English, which is used more and more in business, is also taught earlier and earlier, especially in the German-speaking part of Switzerland. The researchers found that Swiss multilingualism generated 46 billion francs, which is 9% of GDP (Geneva, 2009).

This is the first time the economic value of a country’s language skills has been calculated. Thus, Swiss multilingualism is a source of wealth and not only in terms of culture.

Many studies measure language barriers as trade tariff equivalents. Frankel, (1997) Frankel & Rose (2002), and Heliwel (1999) attempted to measure language differences as trade barriers and have quantified the costs of language barriers as between 15%- 22% in terms of tariff equivalents. They also estimate that sharing a common language can reduce language barriers to bilateral trade by between 75% and 170%.Noguer & Siscart (2003) argue that language barriers vary across sectors: the tariff equivalent of language barriers is close to zero they say in sectors such as agriculture, mining, petroleum refineries, iron & steel and food. However, there are large tariff equivalents of language barriers in printing & publishing (18%); clothing (14%); professional, scientific and controlling equipment (10%). F. Grin showed that the value of multilingualism varies though from one sector to another.

The research report "Les langues étrangères dans l’activité professionnelle" (University of Geneva, 2009) listed the key figures in the table above showing the effects of multilingualism on different sectors. Multilingualism has the greatest impact on IT services (22.67%). Chemistry, transport and mechanical engineering hold a second position with 16.20%, 16.03% and 15.31%. Manufacturing and finance occupy a third place with 12.33% and 11.92%. In public administration and retailing multilingualism is less important (2.84% and 3.45%).

3.2 The micro-economic dimension

The economics of multilingualism has also been defined at a micro-economic level. The micro-economic analysis model was developed mainly in connection with the measurement of export effects of lack of language skills in business. It is particularly the British Chambers of Commerce and The National Centre for Languages that have launched the model.

The National Centre for Languages, 2009

The British Chambers of Commerce language survey (2004) explicitly looked at the impact of language skills on export performance. It identified four different profiles of export managers based in the UK, taking into account their motivations, ambitions, education and individual language competence and classifying them as: opportunist, developer, adaptor and enabler. These behavioural styles were then linked with different types of export performance in their companies.

The National Center for Languages, 2009

The survey found there was a direct correlation between the value an individual export manager placed on language skills within their business and annual turnover. Only 33% of Opportunists, who valued language skills the least, had an annual export turnover above €750,000. This increased to 54% for Developers, 67% for Adapters and 77% for Enablers, who placed the most value on language skills within their business. Moreover, export sales by Opportunists were declining by an average of €75,000 a year per exporter, while Enablers’ exports were increasing by an average of €440,000 a year per exporter.

The European Commission has studied the impact of language skills on export performance (ELAN: Effects on the European Economy of Shortages of Foreign Language Skills in Enterprise, European Commission 2006). The survey of SMEs in 29 countries found that a significant amount of business is being lost as a result of lack of language skills. Across the sample of nearly 2000 businesses, 11% of respondents (195 SMEs) had lost a contract as a result of lack of language skills. Many were unable or unwilling to indicate the size of the contract lost, but 37 businesses had lost actual contracts which together were valued at between € 8 million and € 13.5 million. A further 54 businesses had lost potential contracts worth in total between €16.5 million and €25.3 million. At least 10 businesses had lost contracts worth over €1 million.

4. The export effects in SMEs of multilingual market communication

4.1 Selecting the surveyed countries: Sweden, Germany and France

The importance of multilingualism varies by sector and industrial structure. Therefore the importance of language barriers for trade is affected by a country’s industrial structure. Sweden, Germany and France have a similar industrial and economic structure and can therefore be compared with regard to the use of export languages among SMEs.

Based on the language of economic analysis I have in this study conducted a comparative analysis of Swedish, German and French small-and medium-sized enterprises. The study is based on statistical data from several national and international sources which will be referred to in each specific table or diagram and list of references.

4.2 Selected variables

- Number of used languages and proportion of SMEs using export languages

- Proportion of SMEs having a multilingual export strategy

- Number of export countries

- Export turnover share

- Market share in the BRIC-countries

- Proportion of exporting SMEs to a specific country

- Proportion of exporting SMEs to various geographic areas

- Number of foreign customers and proportion of SMEs having a foreign establishment

- Proportion of SMEs adapting their website for foreign markets

- Percentage of SMEs missing export contracts due to language barriers.

- Proportion of multilingual inhabitants in each surveyed country

4.3 Other variables taken into account

Exports are affected by many variables other than language. The relationship between export success and use of market languages remains even when taking into account other influential factors. The main intermediate variables that have been considered when studying the role of multilingualism in exports of Swedish, French and German SMEs are:

- Currency Differences

- Macro-economic conditions

- Industry Structure

- Company structure and size of company

- Geographic location and size of the domestic market

- Export prices and production costs

- Outsourcing Strategies

- R & D intensity

5. Language use and export success among Swedish, German and French SMEs

5.1 Multilingual export strategy and loss of export contracts

The proportion of SME companies having a multilingual export strategy is lower in Sweden than in the EU. Multilingual export strategy means that SMEs i) always aim at communicating in the target country’s language in negotiations ii) require office staff to have command of at least one foreign language. The proportion of firms reporting that they miss contracts due to lack of language skills are 20% in Sweden compared with 11% in the rest of the EU. This seems to be correlated with the proportion of SME companies having a multilingual export strategy, 48% in the EU and 27% in Sweden.

In addition, the percentage of companies having a multilingual export strategy are 63% in Germany and 40% in France. This means that the percentage of firms missing export contracts due to language barriers are much lower in Germany (8%) and France (13%) compared to Sweden (20%).

The term multilingualism refers both to a situation in which several languages are spoken within a certain geographical area and to the ability of a person to master multiple languages.

When we compare the proportion of multi-lingual inhabitants in the total population, we discover, however, that Sweden has a higher proportion of multilingual inhabitants than Germany and France. Data taken from the European Commission’s Eurobarometer, "Europeans and Their Languages" (2006), show that the percentage of the population speaking at least one language other than mother tongue are 90% in Sweden compared with 51% in France and 67% in Germany. The proportion of the population speaking at least two languages besides their mother tongue are 48% in Sweden compared with 21% for France and 27% for Germany. Sweden also has a very low proportion of the population who do not speak any other language than their mother tongue, 10% vs. 49% for France and 33% for Germany.

The European Commission, 2006

Sweden has a higher proportion of multilingual inhabitants among the total population compared with France and Germany. Yet the percentage of firms having a multilingual export strategy is relatively low. Here we can talk about a Swedish paradox. The low proportion of SME companies having a multilingual export strategy and the high percentage of firms missing export contract stands in contrast to the high proportion of multi-lingual inhabitants in the population and constitutes a clear indicator that Sweden does not make full use of its language assets regarding exports. The gap between the country’s high proportion of multi-lingual inhabitants and the low percentage of multi-lingual staff at the enterprise level we can call the Swedish language skills’ paradox.

Denmark also differs markedly from France and Germany, but is comparable with Sweden regarding multilingual skills of the population. Denmark has a considerably higher rate of use of multilingualism in the context of export. Among Danish SMEs 68% present a multilingual export strategy compared to only 27% in Sweden.

5.2 Language use in Swedish, German and French SMEs

Among Swedish SMEs only three languages are used: English used by 86% of companies, German used by 25% of companies and French used by 14% of companies. French SMEs make use of at least four languages: English (45%), German (30%), Spanish (10%) and Italian (5%). Other languages are used by 11% of French SMEs (including Portuguese and Japanese).

Elise, 2001, Europages, 2006, 2007, TNP3, National report, Germany 2005 and French National Database.

The German SME companies are the most language-intensive among the comparison countries. German companies’ use of language is divided into frequent use, to some extent, and occasional use. The frequently used languages are English (80.6%), French (33.6%), Spanish (13.3%) and Italian (8.3%). Eight other languages, including Japanese and Chinese are used to some extent. Thirteen other languages, including Turkish, Arabic, Hindi-Urdu, Indonesian are used sporadically.

5.3 High language skills provide better access to emerging markets

Swedish small-and medium-sized enterprises use a smaller number of market languages compared with those in France and Germany. Swedish SMEs export, primarily to neighboring markets, mainly Scandinavia, which restricts the export and makes it vulnerable. SMEs in France and Germany use up to 12 languages, giving them better conditions for market access to emerging markets.

European Commission, 2006, Europages, 2006, 2007, Swedbank, 2006.

The difference in the proportion of exporting SME companies appears to be correlated to the number of languages used by SMEs in each country. The higher the multilingual skills among SME companies, the greater the proportion of firms exporting to emerging markets and the better the export geography. Among German SMEs 43% are exporting to Central Asia, compared with 10% of French SMEs, and 8% of Swedish SMEs. This seems to be correlated with business language skills in Chinese. Among German SMEs 30% are exporting to South America, compared with 13% of French and 8% of Swedish SMEs. This seems to be related to business language skills in Spanish and Portuguese. 41% of German SMEs export to East Asia and Oceania, compared with 28% of French and 14% for Swedish SMEs.

High multilingual skills also provide a larger number of export countries. Greater investment in multilingual staff brings about 10.7 export countries for the German SMEs, and 7.8 export countries for the French SMEs on average. Lower investment in multilingual staff only gives the Swedish SMEs 3.9 export countries on average.

Specific la nguage skills also seem to be associated with higher export performance to separate countries.When we consider the proportion of exporting firms in relation to separate countries, we can notice that Sweden has a significantly lower proportion of SMEs exporting to China, Turkey, Russia and Poland than France and Germany. Although Russia is closer to Sweden, only 12% of Swedish SMEs export there, compared with 29% of German SMEs and 19% of French SMEs. There are only 19% of Swedish SMEs exporting to Poland, compared with 42% of German SMEs. This is an interesting contrast, given that Poland is a neighbor of both Sweden and Germany. Even France has a higher percentage of exporting SME firms to Poland (23%).

European Commission,2006, Europages, 2008, SEB, 2009.

High multilingual skills also seem to give a larger market share in the BRIC countries: Brazil, Russia, India and China. Germany’s market share is 5.6 in China, 5.9 in India, 10.4 in Brazil and 16.8 in Russia.

The corresponding figures for France are 2.1 for China, 3.1 for India, 4.8 for Brazil and 3.5 for Russia. This compared with Sweden’s figures that are at 0.7 for India, 1.2 for Brazil and 1.8 for Russia. Sweden’s market share in China has not developed enough so that it can be included in international trade statistics.

5.4 Multilingual website provides higher export

When SMEs are looking to expand their business globally, Internet or more precisely a multilingual website can greatly help them to reach a global audience. By incorporating multilingual support in their website, companies are greatly increasing their chances to capture more business.

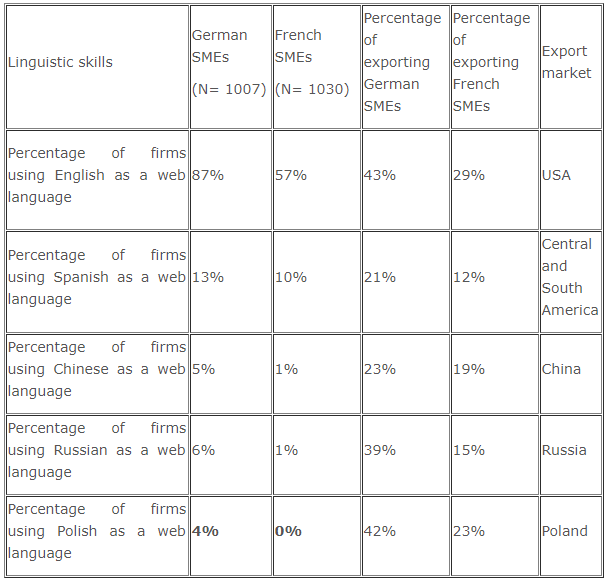

There are no data available for Swedish SME companies concerning website and multilingualism. But when comparing German and French SMEs I find a connection between having a multilingual website and export performance.

The German SME companies present higher web language skills than the French firms. In Germany a larger number of web languages are used by a greater percentage of SME companies. Against this background, it has been possible to further test the hypothesis of export impact of language skills with particular focus on the German and French SME companies web language skills in English, Spanish, Polish, Russian and Chinese. In principle, a larger number of languages and a higher percentage of companies using these at their website should yield a higher proportion of companies exporting to the market where the specific language is spoken.

The table above shows clearly that the German SME companies have a higher percentage of exporting companies to all studied countries and export markets. This appears to be related to a larger percentage of companies presenting web language skills in each market language. In all cases higher web language skills result in a higher proportion of exporting firms.

Higher web language skills give the German SME firms a real advantage in Central and South America. 21% of the German SME companies export to this area, compared with 12% among the French.

Furthermore, the German advantage in Russia and Poland cannot only be explained by Germany’s geographical proximity to these countries. Quite 39% of the German SME companies export to Russia compared with only 15% of the French. Language skills appear to have a bearing on this. Among the French SME companies, only 1% use Russian as a web language, compared with 6% for the German ones.

Germany’s superiority in Poland can be partially explained by geographical proximity, but language skills also play a role. Quite 42% of German companies export to Poland, compared with 23% of the French. 4% among German SMEs use Polish as a web language compared to none for the French. Overall, we can notice that the proportion of SMEs exporting to a certain country or area can be correlated with the percentage of companies using the language of the export market as a web language.

5.5 Language skills provide a higher number of foreign-billed customers

Data from firms about the results (sales, profits) are limited. This is often due to the fact that companies want to protect trade secrets. But enough information is available on the French and German SMEs foreign-billed customers. The number of foreign-billed customers is an indicator that can be used instead of sales to measure the impact of language skills on economic performance of exports.

Higher language skills among German SMEs appear to have direct effects on the number of foreign-billed customers. Among German SME companies, which have higher language skills than French SMEs, the percentage of companies billing more than 50 customers abroad are at 63%. The corresponding figure for France is 15%. Furthermore, 44% of French SMEs invoice between 10 and 49 customers abroad. This is the largest category. Entire 17% have less than five customers abroad.

The corresponding figure for the German SMEs is only 1%. Here we can again observe differences in export performances that seem to correlate with the companies’ linguistic skills in the specific language of the export market.

6. Denmark’s exports of services are higher compared to Sweden due to corporate language skills

Export of services makes heavy demands on language skills among businesses. The export figures for separate countries suggest that the use of fewer market languages may lead to a poorer growth of exports of services. Companies’ qualifications in specific market languages can therefore explain why Denmark has a higher export of services than Sweden.

In this study, I have put forward data at a micro-level to suggest that multilingualism provides export benefits. The same reasoning can be applied at a macro level, particularly regarding exports of services. According to the research field of economics of multilingualism, linguistic skills are most important in the service sector. When we look at Denmark and Sweden, we can notice that Denmark’s exports of services have a better performance than the Swedish. The difference in corporate linguistic skills, when comparing the countries, seem to play a certain role.

Trade in services across national borders is growing faster than trade in many countries. One explanation is that trade in services is less cyclical as many business services are based on long-term contracts. Another explanation is that trade in services to some extent is a-cyclical, that is less affected by economic fluctuations.

Merchandise trade dominates the Swedish foreign trade, but exports of services have in recent decades become increasingly important and now comprises about 25% of total exports. But compared to Denmark, this performance is relatively modest. Over the past ten years, the Scandinavian countries increased their share of exports of services. Denmark is the country that showed the largest increase during the period and the country’s exports of services are currently the largest in the Scandinavian countries and represent 39% of Denmark’s total exports.

Sweden competes with Denmark in the field of health care for example. In both countries, the health care sector constitutes a major service export potential. Yet Sweden is far behind Denmark. Sweden and Denmark’s health and social care is characterized by its high quality. Both the organizational models and services themselves are interesting from an international perspective. There are good opportunities in both countries for the sector to become a more important export industry. Examples of services that can cross the border are some types of diagnostics, information technology solutions to health care management systems and service / support to medical devices.

Global aid activities in the health and social services are an increasingly growing area. In this area, we can notice that Denmark has 10 times the share of UN procurement than Sweden. Of the UN’s total procurement (goods and services) in 2007 Denmark’s share was 2.46 percent, while Sweden’s share was 0.2 percent. Looking only at the UN’s procurement of services, Denmark’s share was 1.29 percent, compared to Sweden’s share of 0.12 percent.

6.1 Corporate language skills behind the higher exports of services in Denmark

The difference between the Danish and Swedish exports of services becomes even clearer when we compare different export destinations. In 2008, Denmark’s exports of services to Germany amounted to a value of 36 billion Danish crowns. In the same year, Sweden’s exports of services to Germany represented a value of 12.4 billion Swedish crowns. When we look at corporate language skills, we cannot exclude that the high percentage of Danish companies using the German language as a market language may be behind the fact that Denmark’s exports of services to Germany are three times higher than Sweden’s . According to existing statistical data 25% of Swedish companies use German as a market language compared with 80% of Danish companies.

In 2008, Denmark’s s exports of services to Sweden amounted to a value of 37 billion Danish crowns. In the same year Sweden’s exports of services to Denmark represented a value of 9.9 billion Swedish crowns. Denmark’s exports of services to Norway that same year amounted to 22 billion Danish crowns compared to 13.1 billion Swedish crowns for Sweden.

When we look at corporate language skills, we cannot exclude that the high percentage of Danish companies using a Scandinavian language may be the reason why Denmark’s exports of services to Sweden are four times higher than Sweden’s service export to Denmark. According to statistics from the Danish Industry about 50% of Danish companies use Norwegian or Swedish when trading with these countries.

Several factors may explain the fact that Denmark’s export of services perform better than the Swedish. But corporate language skills are likely to have a significance. Swedish companies use mainly English and German and French. Danish companies use English, German, Scandinavian languages, French, Spanish, Russian, Chinese, Arabic, Polish, Portuguese and Italian. International statistics (WTO 2008) show that Britain, Germany and France rank second, third and fourth among the world’s largest exporters of services. Companies in these countries make use of between 6 and 12 market languages.

6.2 The Chinese language is becoming increasingly important for foreign trade

The importance of language skills for exports will become more and more important as four out of five start-ups today are service companies. This is particularly true for the world’s largest economic growth market China. In 2008, the value of Sweden’s exports of services to China amounted to 7.3 billion Swedish crowns. In the same year, Denmark exported to a value of 14.5 billion Danish crowns. The fact that Denmark’s export of services is twice as high as the Swedish can also probably be explained by the fact that 10% of Danish companies use Chinese as a market language. There are no corresponding statistical data for Swedish companies, but most reports show that Chinese constitutes a substantial trade barrier for Swedish exports to China.

The English language is no longer dominant in world trade and internet traffic. The English language’s role as the sole language for international business relations has declined and more and more companies use other languages, particularly the specific language of the export market. The importance of the Chinese language for trade relations has grown in less than ten years from 5% in 2000 to 20% in 2009. Meanwhile, the English language’s importance has declined from 51% in 2000 to 29% in 2009. Against this background, Chinese has to be regarded as a new modern language, on a par with German, French and Spanish. Chinese should therefore in the future be a selectable option among other contemporary languages in high school and at the university.

7. Policy Conclusions: what needs to be done in the short and longer term?

The effects of multilingualism on exports involve a number of policy conclusions when it comes to promoting exports.

7.1 At the national level

In order to reduce dependence on neighboring markets measures to promote multilingualism need to be taken at the national level. In the short term, efforts need to be made reducing language barriers to market entry and facilitating the small-and medium-sized companies access to new emerging markets through supporting and financing professional development programs and language training.

Longer-term measures concern in particular the adaptation of education to the needs of employers through education to a greater number of languages, particularly at secondary and university levels. The languages of the migrant employees also provide a shortcut to multilingualism in order to increase small-and medium-sized companies’ exports to new emerging markets.

7.2 At the corporate level

Companies need to improve their multilingual export strategies, business communication and recruitment strategies :

7.2.1 SMEs need to keep a record of staff language skills and exploit and develop the linguistic skills available within their company.

7.2 2 Recruitment of new staff should consider language skills. In order to deal with customers abroad SMEs need to acquire staff with specific language skills in an early stage when they plan to begin trading in new foreign countries.

7.2.3 SMEs need to adapt their website for foreign markets. Making sure their website is multilingual when choosing to trade internationally give a better access to customers abroad.

7.2.4 In order to avoid missing export contracts due to judicial miss interpretation and language miss understanding SMEs need to employ external translators/interpreters for foreign trade.

8. General policy considerations

Small-and medium-sized enterprises’ importance for foreign trade grows. There is also a clear link between export / import and employment rate. Since small-and medium-sized enterprises represent nearly 99% of the total number of companies in Europe, one could imagine that if more small companies became successful export companies and those which are already exporting got even better, this could have a significantly affect on employment. Small - and medium-sized enterprises’ export performance is of strategic importance in order to reduce vulnerability within the field of exports and employment.

In this study I have shown that there is a link between multilingualism and export success of SMEs. This leads to a number of policy conclusions with regard to promoting exports and reducing dependence on neighboring markets.

Enhanced policy development requires a picture of SME companies needs of market languages at the national level. This concerns especially the need for multilingual market communication and recruitment strategies, language training and professional development programs, and Web communications in enterprise.

France and Germany are important competitor countries to learn from in terms of SME enterprises’ multilingual export strategies. Another source of inspiration when it comes to multilingualism and exports is Denmark. Both Swedish and Danish are small languages. This means that these countries are comparable in terms of language barriers to market entry, despite differences in industrial structure.

While the Swedish SME company makes use of three languages, the number of languages used among Danish companies amount to 12. The percentage of companies presenting a multilingual export strategy is 68% in Denmark and 27% in Sweden. In Denmark, 95% of companies use English in their business relations compared to 86% in Sweden. German is used by 80% of companies compared to 25% in Sweden. French is used by 32% of Danish companies compared to 14% in Sweden.

The percentage of the remaining market languages used by Danish SME’s are: Scandinavian languages 51%, Spanish 19%, Russian 10%, Chinese 10%, Arabic 4%, Polish 4%, Portuguese 3% and Italian 2%.

More than half of the Danish companies have in recruiting personnel with language skills hired people who speak the market language as a mother tongue or who have lived in any of the companies’ export countries. There is a clear preponderance of staff with the corresponding Swedish Ph D in language. Only a fifth of companies recruit staff with a B.A. degree in language from Business schools. Only a tenth recruit staff with a B.A. degree in language from the universities. Among the criteria for recruitment is that language skills being formal or not have to be combined with other education such as sales, marketing and communications.

Bibliography

Main references

CILT, the National Centre for Languages: "Why languages matter", London Country Report, 2005: China Business Forecast Report. London, UK: Business Monitor International

Dansk Industri, 2008: Mere end sprog

European Commission, ELAN, 2006: Effects on the European Economy of Shortages of Foreign Language Skills in Enterprise

European Commission, 2006: Europeans and Their Languages

Europages, 2006: Les PME françaises face à l’exportation. Europe, Internet et spécificité française

Europages, 2007: Les PME allemandes face à l’exportation. Europe, Internet et spécificité allemande

Europages, 2008: France, Allemagne, Italie, Espagne: "Profil et comportement des PME utilisatrices d’internet à l’international"

Grin, F., 2006: Aspects économiques du plurilinguisme, journée des langues de la Chancellerie fédérale, Berne

Grin, F., 2009: The Economics of the Multilingual Workplace, Routledge Studies in Sociolinguistics

Grin, F., Vaillancourt, F., Sfreddo, C., 2009: Qu’en est-il des compétences en langues étrangères dans l’entreprise? Report finals, the Swiss National Science Foundation

Grin, F., Vaillancourt, F., Sfreddo, C., 2009: Langues étrangères dans l’activité professionnelle (LEAP), Rapport final de recherche, Université de Genève

Hallin, E., Nömmik, E.,2008: Marknadsinträde i Kina? – de svåraste inträdesbarriärerna för svenska företag vid marknadsinträde i Kina-, Företagsekonomiska institutionen, Uppsala universitet

Kommerskollegium, 2009: BRIC-länderna i världshandeln. Brasilien, Ryssland, Indien och Kina i fokus

SEB, 2009: Globaliseringen ökar bland småföretagen

Stein, P., 2007: Världsekonomins nya tillväxtmarknader – underskattad potential för svenska företag, Swedfund skriftserie, Stockholm

Swedbank, 2006: Småföretagens utlandsetablering – myter och verklighet, Stockholm

Further references

Bain, J. S, 1956: Barriers to New Competition. Cambridge, Mass, USA: Harvard University Press

Bardaji, J. and P. Scherrer (2008), “Mondialisation et compétitivité des entreprises françaises. L’opinion des chefs d’entreprise de l’industrie’, INSEE Première, No. 1188, May.

Besér, N, 2008: “Skev världsbild får svenska bolag att missa affärer’, Dagens Nyheter, Ekonomi, 2008-04-07, s. 5

BIT (2007), “Les Discriminations à raison de ’l’origine’ dans les embauches en France – Une enquête nationale par tests de discrimination selon la méthode du BIT.’ Genève, Bureau International du Travail

Boulhol, H. (2006), “Le bazar allemand explique-t-il l’écart de performance à l’export par rapport à la France ?’, in P. Artus and L. Fontagné, Évolution récente du commerce extérieur français, Conseil d’analyse économique

Boulhol, H. and L. Maillard (2006), “Analyse descriptive du décrochage récent des exportations françaises’, in P. Artuis and L. Fontagné, Évolution récente du commerce extérieur français, Conseil d’analyse économique

Bouyoux, P. (2008), “Commentaire’, in L. Fontagné and G. Gaulier, Performances à l’exportation de la France et de l’Allemagne, Conseil d’analyse économique

Brodersen Hans (2008) Le “modèle allemand’ à l’exportation : pourquoi l’Allemagne exporte-t-elle tant ? Comité d’études des relations franco-allemandes

Cavusgil, S. T, et al, 2002: Doing Business in Emerging Markets. Kalifornien, USA: Sage Publication Inc

Chiswick, B.R., 2008: The Economics of Language: An Introduction and Overview, Discussion Paper No. 3568, IZA, Bonn, Germany

Deutsche Bank, 2007, Investing in Diversity. One bank, many perspectives.

ELISE, 2001, European Language and International Strategy Development in SMEs, European Overview Report

Ensign, P. C, Robinson, N. P, 2008: “Blackberry in Red China: Research in Motion Navigates Institutional Barriers in an Emerging Market’, Thunderbird International Business Review.Vol. 50, nr. 2, s. 129-142

Erkel-Rousse, H and M. Sylvander (2008), “Externalisation à l’étranger et performances à l’exportation de la France et de l’Allemagne’, in L. Fontagné and G. Gaulier, Performances à l’exportation de la France et de l’Allemagne, Conseil d’analyse économique.

Erkel-Rousse, H. and M. Sylvander (2007), “Performances à l’exportation exceptionnelles et faiblesse de la demande intérieure : l’apparent paradoxe allemand’, L’Économie Française, Comptes et Dossiers, Edition 2007-2008, INSEE-Références

Fontagné, L. and G. Gaulier (2008), Performances à l’exportation de la France et de l’Allemagne, Conseil d’analyse économique

Frankel, J. och Rose, A.K., 2002: An estimate of the effect of common currencies on trade and income, Qrtly Journal of Economics, 117(2), 437-466

Föreningssparbanken Analys, 2006: Utnyttja handelspotentialen i Östersjöregionen

Gassman, O, Han, Z, 2004: ’Motivations and Barriers of Foreign R&D Activities in China’, R&D Management. Vol. 34, nr. 4, s. 423-437

Geroski, P. A, 1991: Market Dynamics and Entry. Cambridge, Mass, USA: Basil Blackwell Inc

Harrigan, K. R, 1981: ’Barriers to Entry and Competitive Strategies’, Strategic ManagementJournal. Vol. 2, nr. 4, s. 395-412

Hatzigeorgiou, A., 2009:"Migration och handel-uppmuntrar invandring utrikeshandel?" Ekonomisk debatt, nr 7, s. 23-36. Stockholm

Henderson, J.K., 2005: Language diversity in international management teams, International Studies of Management and Organisation, vol. 35, nr 1, s, 66-82

Hilmersson, M, 2007: "The impact of language on the emerging market process of SMEs- The case of swedish SMEs establishing business relationships in Poland",9th Vaasa Conference of International Business

Holden, N., 2001: Towards redefining cross-cultural management as knowledge management

Holden, N., 2004: Why marketers need a new concept of culture for the global knowledge economy, International Marketing Review. Vol.21, issue:6, s.563-572.

International Trade Center (2007) Innovations in Export Strategies – Gender Equality: The gender dimension of export strategy. Geneva

Jusko, J, 2004: “Report Outlines Foreign Trade Barriers’, Industry Week. Vol. 253, nr. 5, s. 18-19

Karakaya, F, Stahl, M. J, 1991: Entry Barriers and Market Entry Decision. New York, USA: Greenwood Publishing Group Inc

Le Figaro, 2008.02.29: L’Allemagne moins tentée par les délocalisations, Paris

Ministere de la Culture et de la Communication, 2008: Multilinguisme, compétitivité économique et cohésion sociale, Paris

Noguer, M. och Siscart, M., 2003: Language as a Barrier to International Trade? An Empirical Investigation, Second Job-market Paper, nov. 2003

Nutek, 2009: Svenska småföretags internationalisering, Kartläggning och analys, Stockholm

Porter, M. E, 1980a: Competitive Strategy. New York, USA: Free Press

Porter, M. E, 1980b: “Industry Structure and Competitive Strategy, Financial Analysts Journal. Vol. 36, nr. 4, s. 30-41

REFLECT, 2002, "Comparative Overview of Survey Results"

Riberio, R., 2007: "The language barrier as an aid to communication", Social studies of science, vol.37, nr.4, 561-584

Rose, A.K.,2001: "Currency Unions and Trade: the effect is large", CEPR Economic Policy Nr 33, s. 449-461. okt.

RTP-partnerskapet i Stockholms län, 2005, Östersjöstrategi för Stockholm-Mälarregionen, Stockholm

Sauter, N., 2008: Talking Trade: Language Barriers in Intra-Canadian Commerce

Sheikh, H. & Kenny, B. (2001, March). European Language & International Strategy Development in SMEs: A Comparative Analysis of Language Strategies in Ireland & Northern Ireland, Denmark,the Netherlands, Scotland and Sweden. Paper presented at CIBER 2001 The Conference on Language, Communication and Global Management, San Diego, CA

SOU 2008:56: Mångfald som möjlighet – Utredningen om ökad integration inom de gröna näringarna

SOU 2008:90: Svensk export och internationalisering. Utveckling, utmaningar, företagsklimat och främjande. Betänkande av Exportutredningen. Stockholm

TIBEM, 2006: Entreprises bruxelloises et langues étrangères. Pratique et cout d’une main d’œuvre ne maîtrisant pas les langues étrangères. Rapport de recherche, Bruxelles

TNP3 (Thematic Network Project in the Area of Languages III), 2005, Sub-project Three: Languages for Enhanced Opportunities on the European Labour Market, National report, Germany

Vaara, E., Tienari, J., Piekkari R.& Säntti R., 2005: "Language and the circuits of power in a merging multinational corporation", Journal of Management Studies, 42(3) s. 595-623